Archived -

Economic Overview

Sound Economic Stewardship in Uncertain Times

On this page:

Around the world, the aftershocks of a once-in-a-century pandemic, combined with external factors including Russia’s illegal invasion of Ukraine, have driven inflation to its highest rates in decades. Canadians are feeling the pinch—at the grocery store, when bills arrive at the end of the month, and when they think about what the future holds.

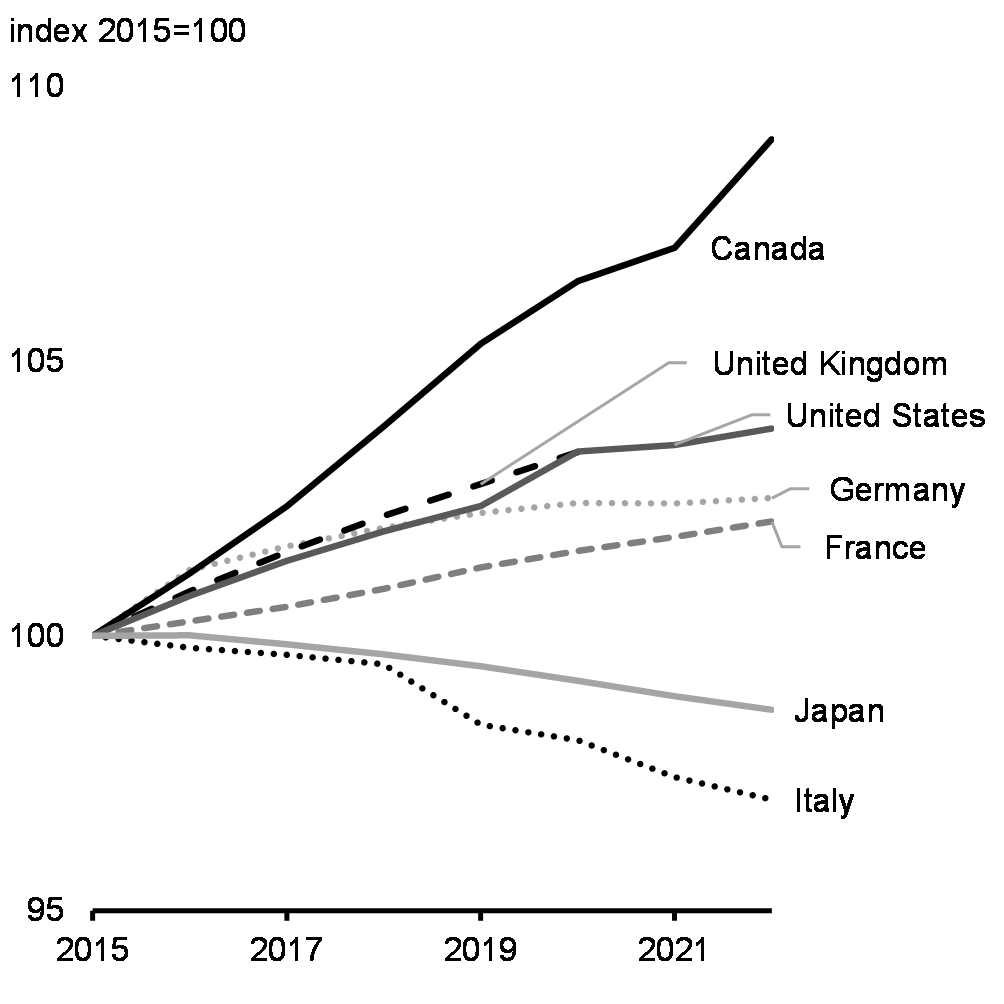

Despite the challenges we face, Canadians can be confident that our economy will withstand the global economic slowdown that lies ahead. Canada’s unemployment rate is at multi-decade lows, and economic growth has outperformed our G7 peers so far this year. Programs that supported Canadians through the pandemic helped provide the foundations for an unprecedented economic recovery. This will ensure that Canada will face global economic headwinds from a position of fundamental economic strength and resilience.

At a time of elevated inflation, the government has taken a balanced approach in helping people cope with the rising cost of living. Significant, targeted measures have been provided to support the most vulnerable while still ensuring that Canada maintains the fiscal firepower required in these uncertain times.

In the challenging economic landscape that Canada and the world are contending with, economic growth—both here and around the world—is expected to slow. The severity of the slowdown, both in Canada and abroad, will depend critically on how quickly inflation moderates.

In the years to come, structural trends suggest supply will remain an important constraint on global growth. The future will be marked by an ongoing reorientation of global trade patterns, a rapidly aging population, and the dual imperatives of energy security and the transition to net-zero. Investing in measures that encourage middle class job creation and new investment will be key to the future prosperity of workers and businesses in Canada.

The 2022 Fall Economic Statement builds on actions the government has taken to address these essential challenges, while focusing on supporting workers and families through a challenging economic time. And as we work together to weather the economic slowdown to come, the 2022 Fall Economic Statement will help ensure that our economy can create good-paying jobs for workers, and that we maintain the fiscal firepower we need to support Canadians, grow the middle class, and build an economy that works for everyone.

1.1 New Challenges for the Post-COVID Recovery

Inflation Is the Top Global Economic Challenge

Inflation has increased sharply across the world over the past year. Global imbalances between supply and demand, which stem from a series of global supply shocks combined with rebounding demand, are driving up prices for goods and services.

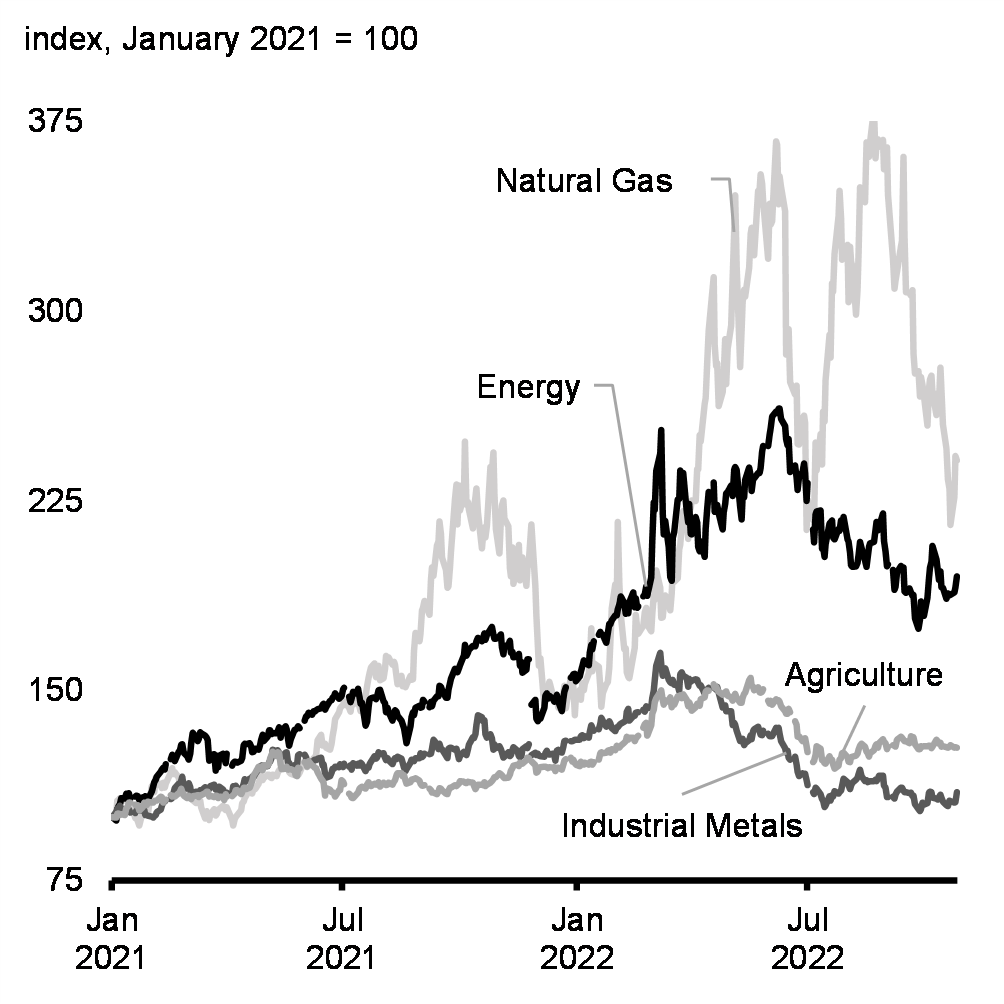

Russia’s illegal and barbaric invasion of Ukraine has disrupted global supply chains and led to a surge in commodity prices, particularly for crude oil, natural gas, food, and agricultural products. Europe is now facing an acute energy crisis as it moves away from dependency on Russian energy, which is driving up manufacturing costs and putting pressure on household budgets. Lockdowns related to China’s zero-COVID policy have prolonged supply chain disruptions. As well, in many advanced economies, including the United States and Canada, inflation pressures have started to broaden with stronger domestic demand and higher wage pressures stemming from tight labour markets.

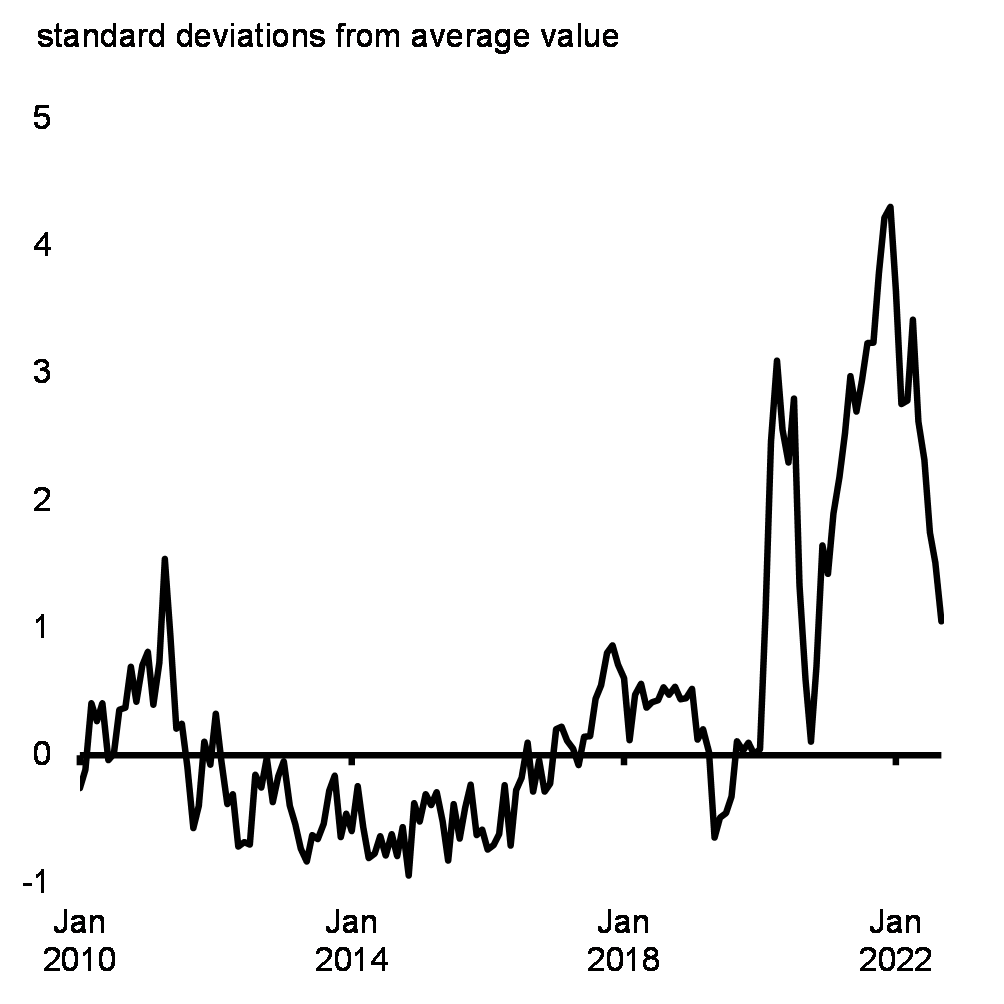

In recent months, some of the global drivers of inflation have begun to ease. Global supply bottlenecks remain elevated but have begun to improve (Chart 1.1) and a range of global commodity prices, including crude oil and agricultural commodities, have fallen from previous highs (Chart 1.2).

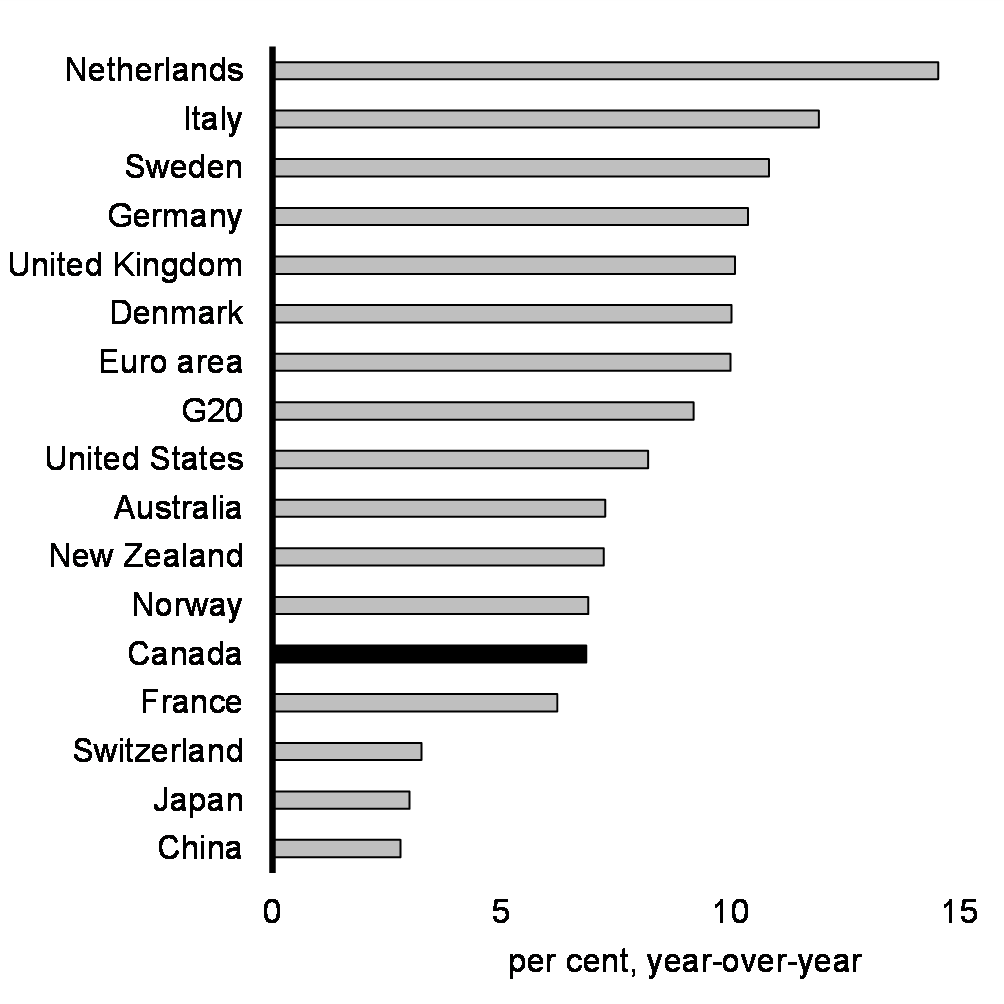

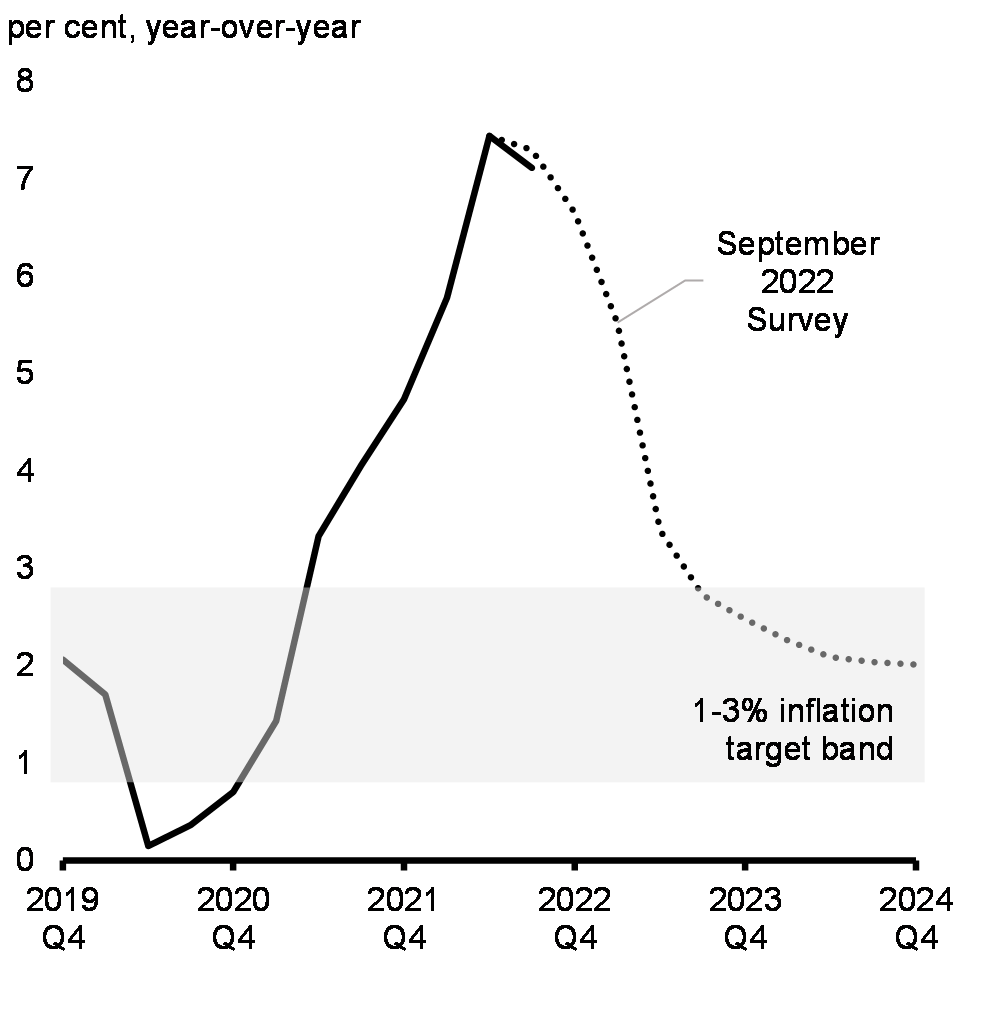

As a result, headline inflation modestly declined in some countries over the summer, including Canada, though it continued to accelerate in other countries, including Italy, Germany, and the U.K. In Canada, headline inflation declined for the third month in a row to 6.9 per cent year-over-year in September, below the 8.1 per cent peak in June, and more moderate than many peer countries (Chart 1.3). That said, inflationary pressures remain high and widespread in Canada. Momentum in core measures of inflation has eased, but core measures remain elevated and inflation is expected to remain above target levels for some time (Chart 1.4).

Global Supply Chain Pressures Index

Commodity Prices

Indeed, there are still significant challenges to the inflation outlook around the world, most notably in the United States. The global economy remains highly disrupted by energy shortages and effects of the war in Ukraine. Global demand remains elevated, as do inflation expectations. It is unlikely that inflationary supply chain pressures will fully abate until demand for goods in the United States—the world’s largest economy—has normalized. The full effect on inflation of higher interest rates is expected to take time to materialize. Altogether, these trends suggest that the global path back to moderate inflation will be gradual.

Consumer Price Inflation in Selected Economies and Regions

Actual and Forecast Consumer Price Inflation, Canada

Interest Rates Are Rising Around the World

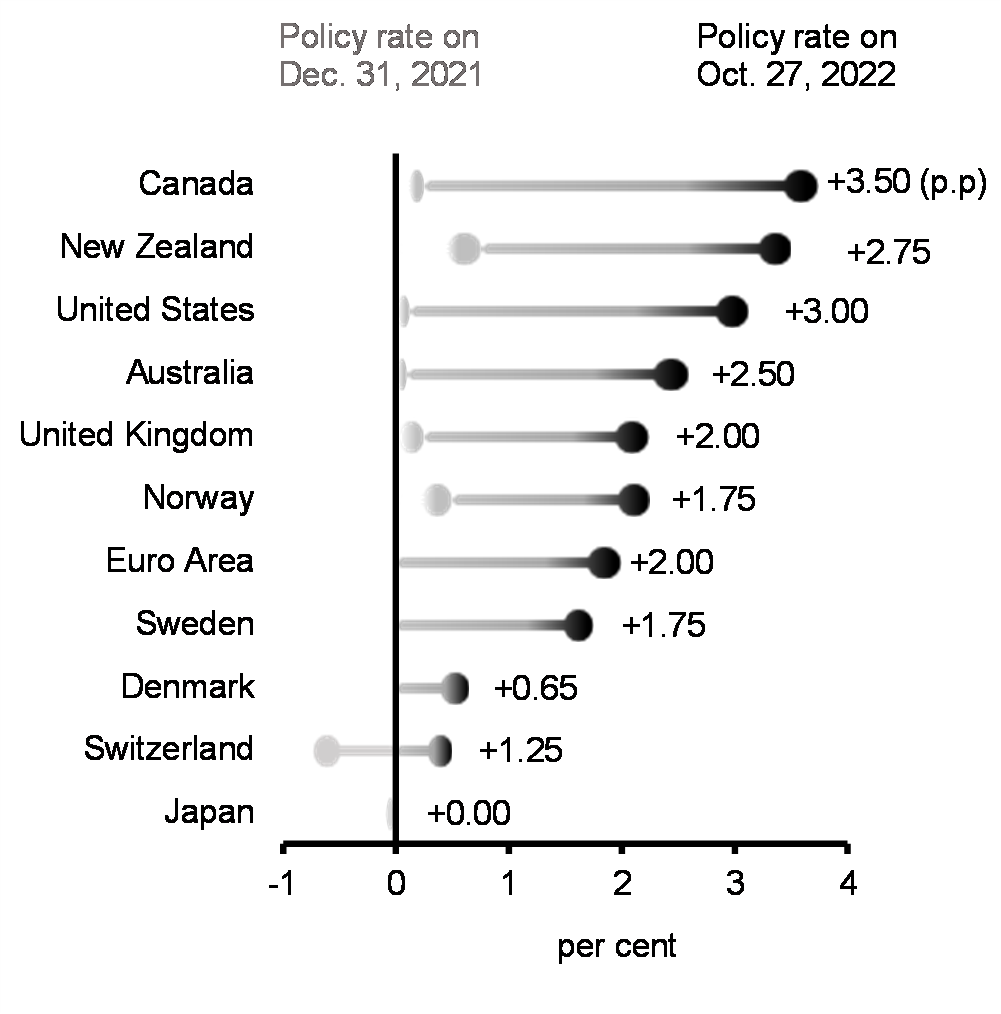

To slow demand and anchor inflation expectations, central banks, including the Bank of Canada and the U.S. Federal Reserve, have been raising interest rates in one of the most synchronized monetary tightening cycles in decades (Chart 1.5). For many advanced economies, interest rates are now reaching levels not seen in nearly 15 years.

Change in Central Bank Policy Rates Since January 2022, Advanced Economies

U.S. Policy Rate Expectations

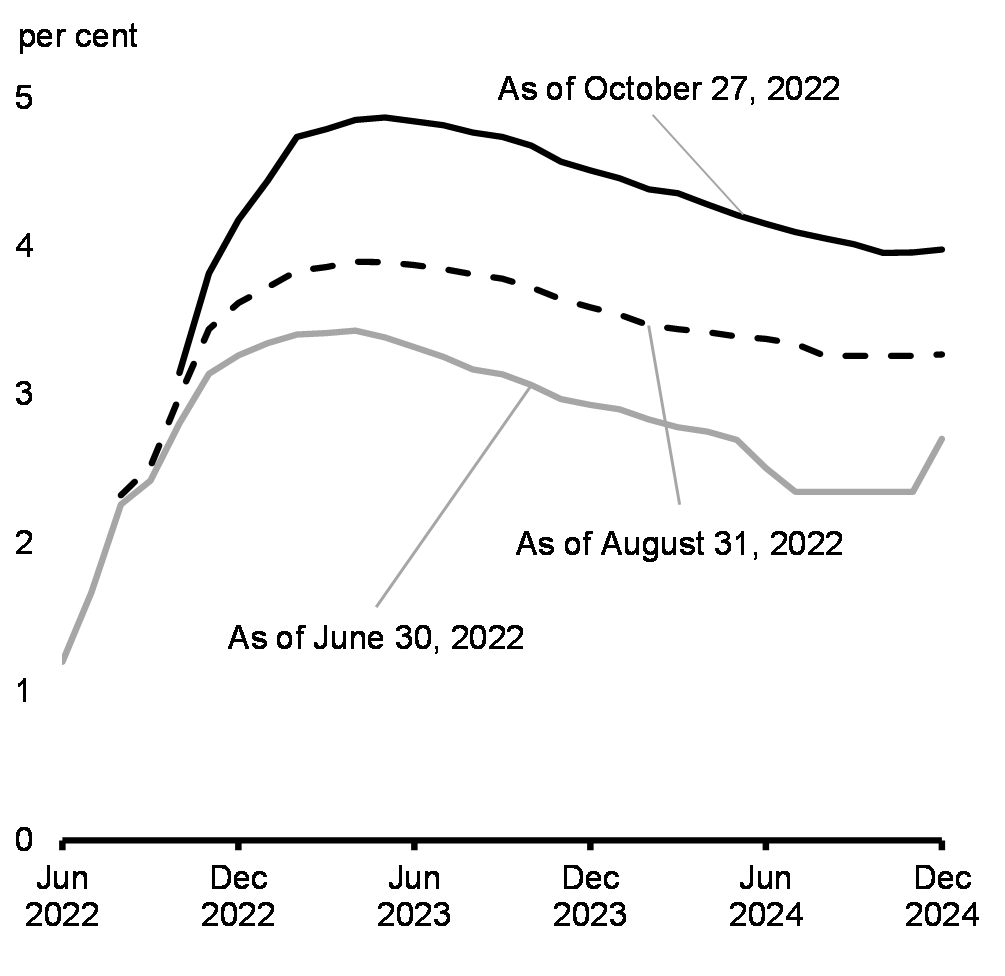

In recent months, market expectations for future policy rates have increased substantially, as underlying inflation and inflation expectations have remained elevated and the U.S. Federal Reserve has shown increased resolve to tame inflation. The ramifications are being felt worldwide in a surging U.S. dollar, rising interest rates, and volatile financial markets. Only a few months ago, U.S. policy rates were expected to peak just above 3 per cent, while markets now see them peaking at nearly 5 per cent (Chart 1.6). Central banks have also largely ended quantitative easing programs, with some allowing their balance sheets to shrink, drawing down liquidity. Primarily in response to the shift in monetary policy and expectations of further rate hikes, financial markets have undergone a notable repricing, with equity markets in particular registering significant declines. Higher interest rates have been deployed by central banks to fight inflation, but will markedly slow economic growth.

The Bank of Canada has been clear that it remains committed to using its monetary policy tools to return to the 2 per cent target and keep inflation expectations well-anchored. In late October, the Bank of Canada reiterated that it expects inflation to decline to around 3 per cent, the upper bound of its inflation target, in late 2023, and return to 2 per cent by the end of 2024.

Global Growth Is Expected to Slow and Recession Risks Have Risen

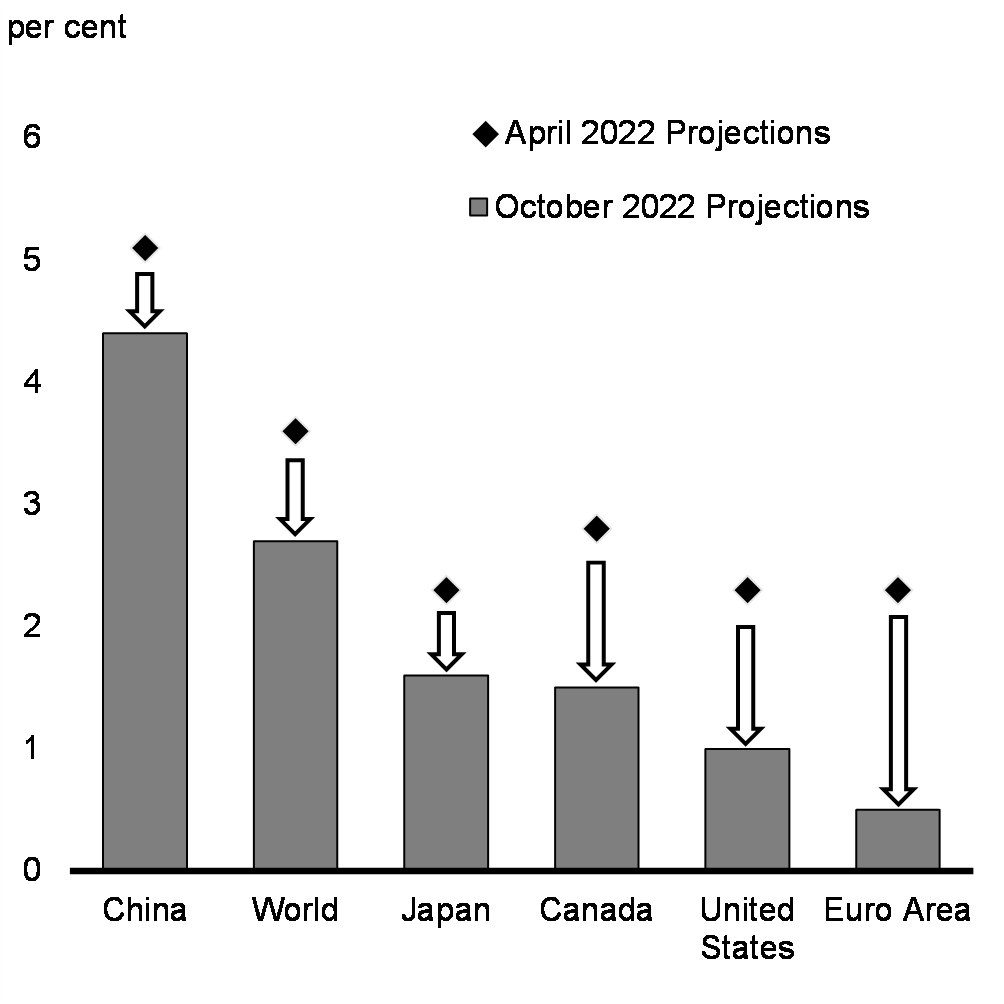

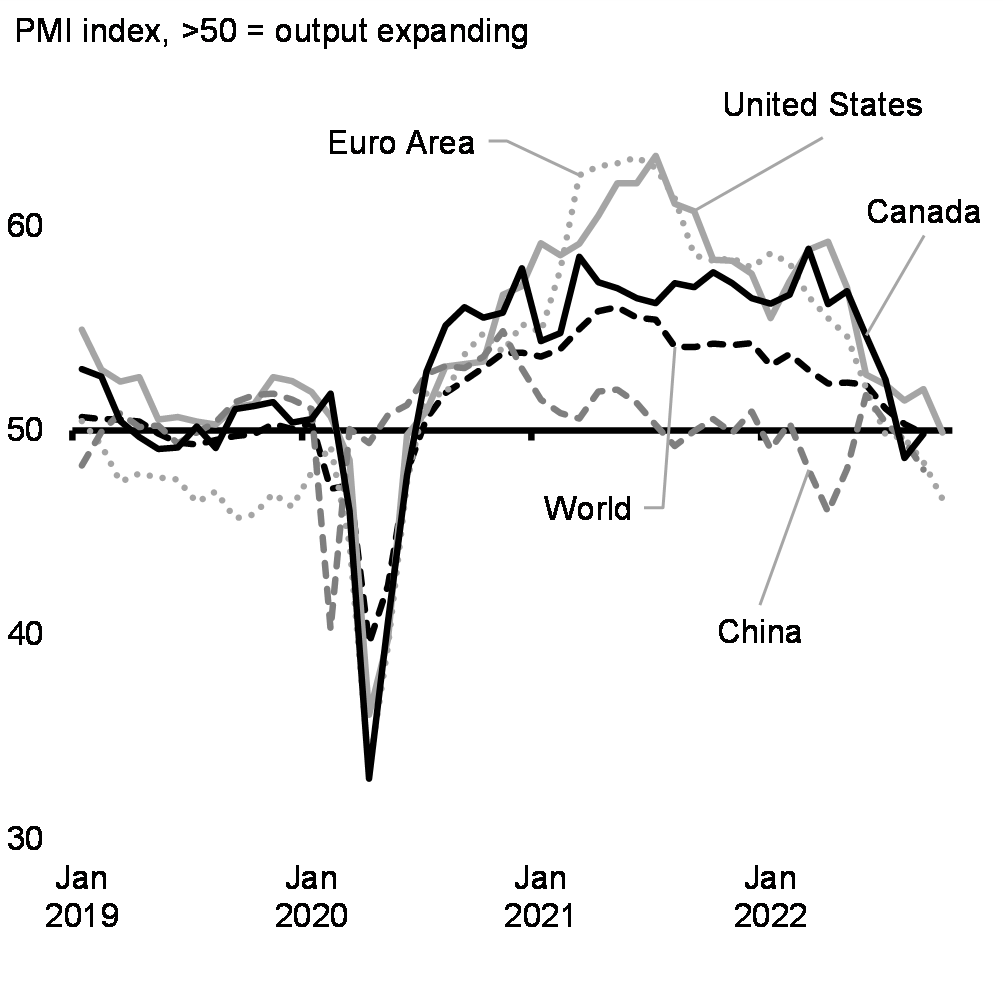

Global growth is expected to slow sharply in the second half of 2022 and in 2023, with the global economy at risk of falling into recession (Chart 1.7). The substantial tightening of financial conditions, as well as the European energy crisis driven by Russia’s illegal invasion of Ukraine, are the main sources of slowing growth in many economies. There are signs that global business activity has begun to weaken (Chart 1.8) and consumer confidence has deteriorated. However, it takes time for tighter financial conditions to have their full effect on production, investment, and consumption decisions. As a result, there is uncertainty about how much global growth will slow.

The sharp rise in U.S. interest rates, coupled with growing concerns over global growth, has fueled a sizeable appreciation of the U.S. dollar against most major currencies, including the Canadian dollar, adding to the increase in prices for imported goods. Given the dominant role of the U.S. dollar in international finance, a strong dollar is also raising debt service costs for non-U.S. borrowers who have debt denominated in U.S. dollars. As a result, developing countries will most acutely feel spillover effects from tightening U.S. monetary policy.

In some major economies, the effects of tighter financial conditions are amplified by unique challenges. The energy crisis in Europe threatens to tip its economy into recession this winter. China is undergoing a marked slowdown in growth amid a necessary correction in its property sector and, at the same time, ongoing restrictions to contain resurgent waves of COVID-19.

Revisions to 2023 Real GDP Growth IMF Forecasts for Major Economies

Global Manufacturing Activity

Canada Has Seen a Strong Recovery

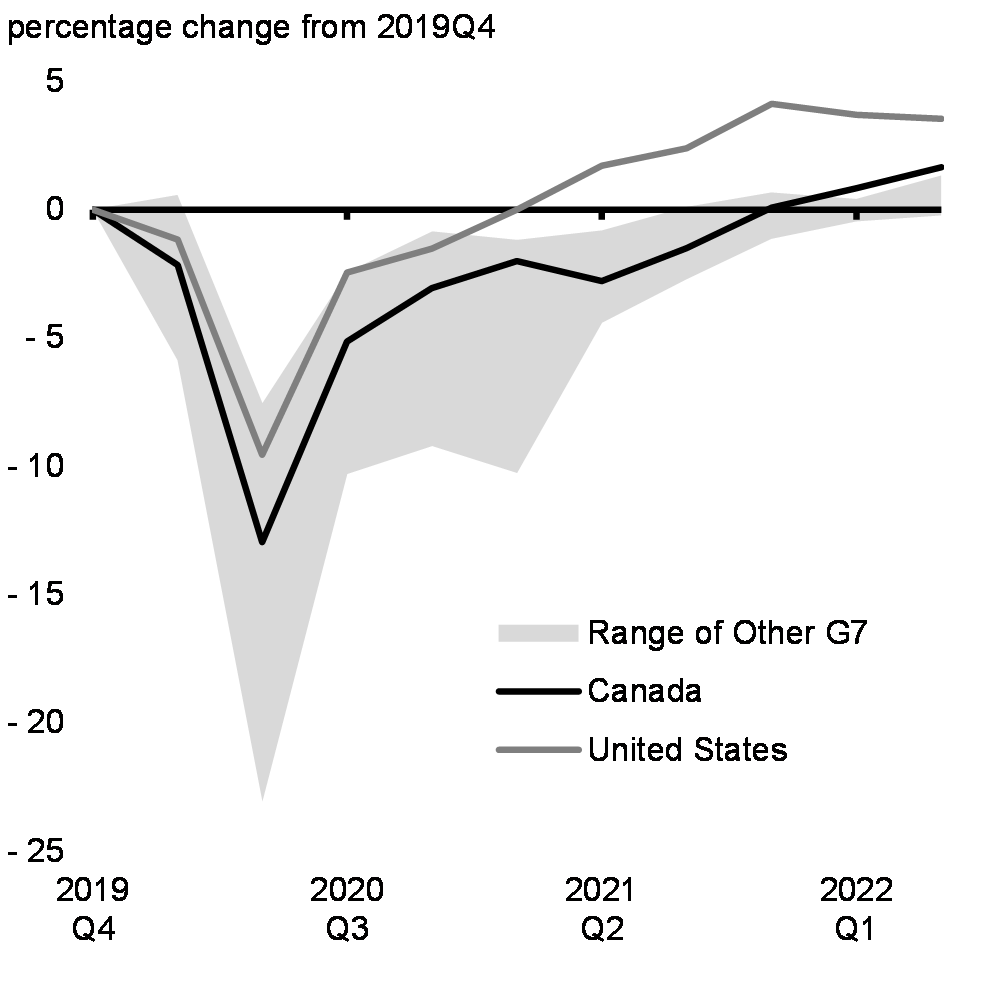

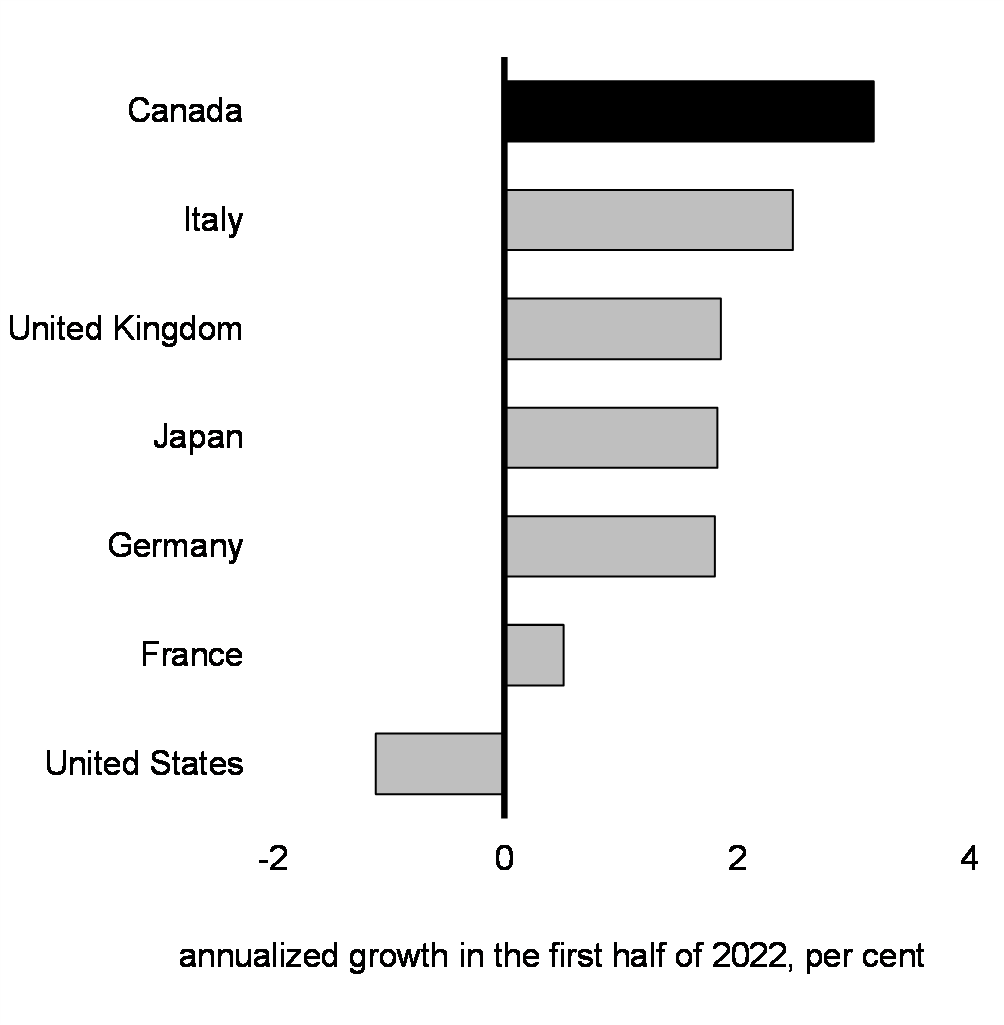

Canada’s economic recovery from the pandemic recession has been strong, with real gross domestic product (GDP) having returned to pre-pandemic levels in the fourth quarter of 2021—the fastest recovery of the last three recessions. Despite slowing global economic growth, the Canadian economy has demonstrated resilience, having seen strong growth in the first half of 2022 (Chart 1.9), with real GDP growing by 3.2 per cent at an annual rate—by far the fastest pace in the G7 (Chart 1.10). Canada’s economy is now 102.6 per cent the size that it was before the pandemic.

Real GDP Recovery From Pandemic in G7 Economies

Real GDP Growth in G7 Economies, 2021Q4 to 2022Q2

The Labour Market Is Strong

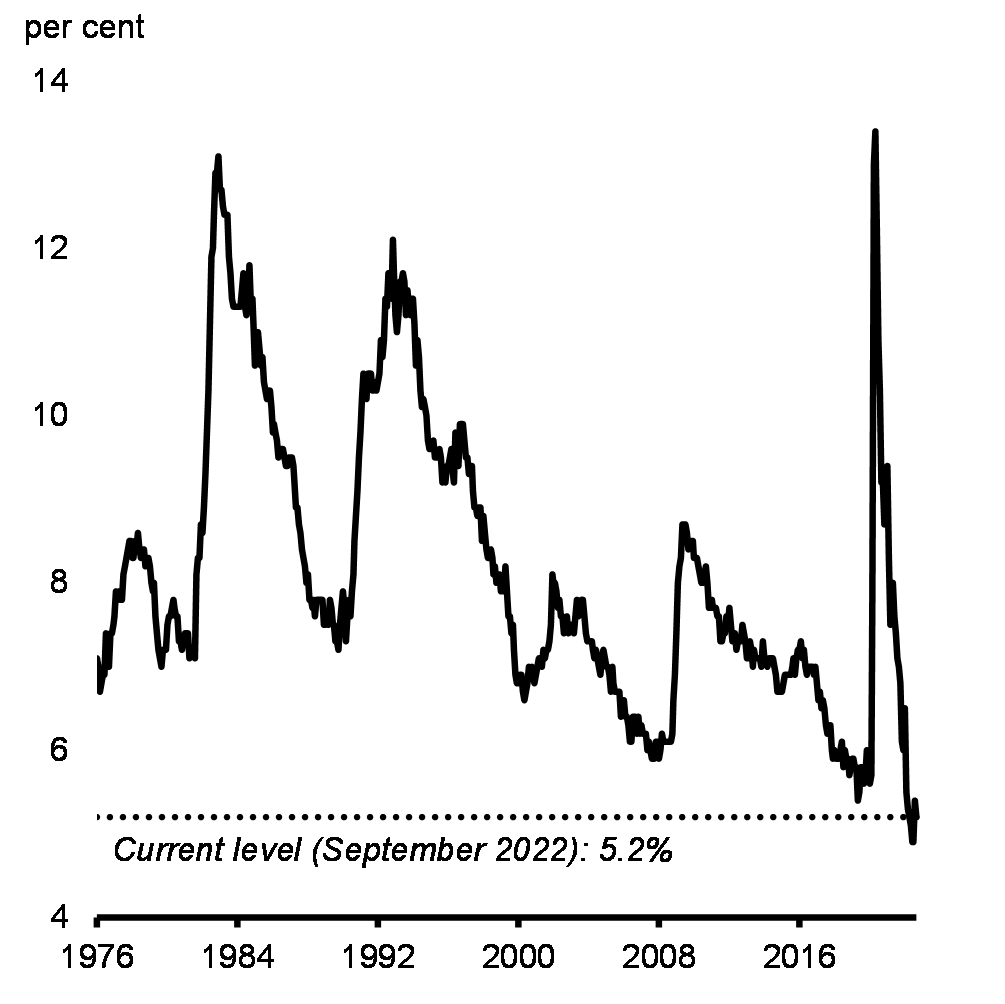

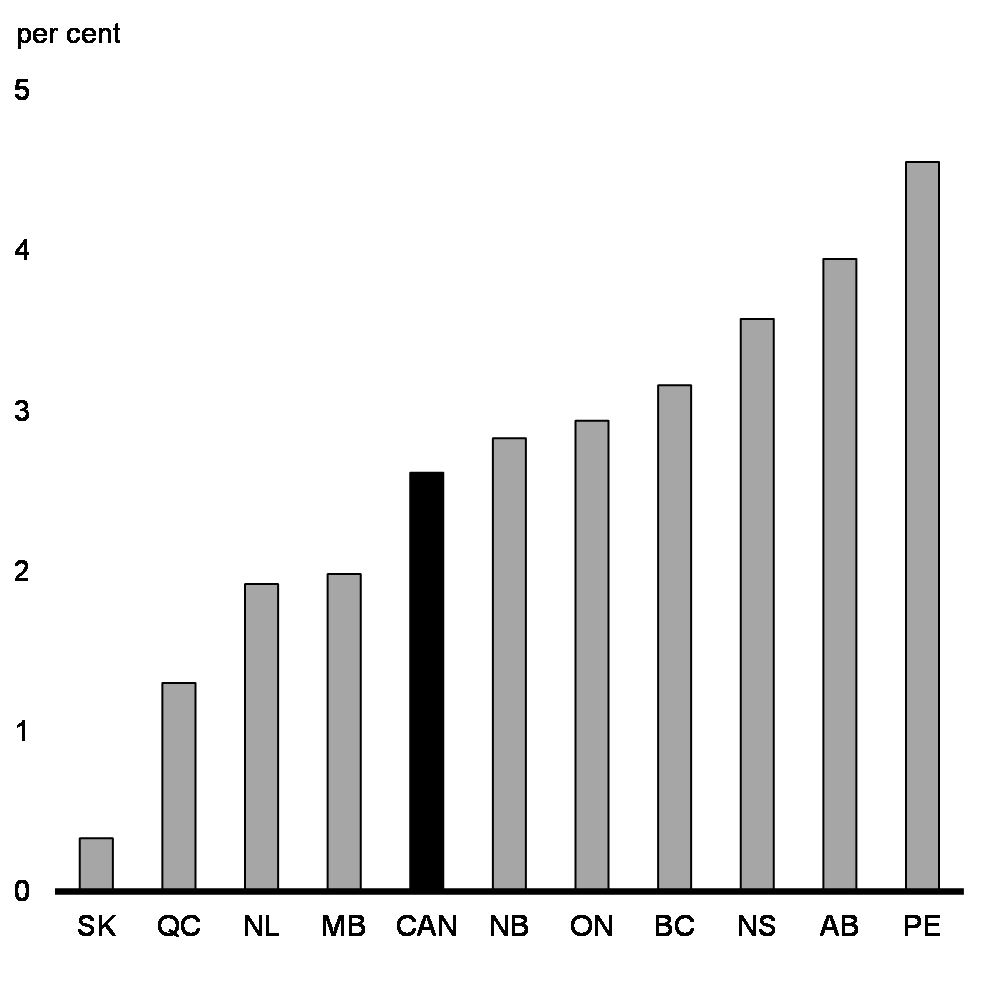

The strength of Canada’s recovery has been particularly evident in the labour market. Canada has seen one of the fastest jobs recoveries in the G7, in large part due to the broad-based pandemic support the federal government provided to workers and businesses. About 400,000 more Canadians are working today than before the pandemic, and the unemployment rate of 5.2 per cent in September is near its record low (Chart 1.11). These strong conditions are apparent across the country, with employment above pre-pandemic levels in every province (Chart 1.12). Compared to the United States, the economy to which Canada’s is most closely linked, labour force participation is particularly strong. In Canada, about 79 per cent of working-age Canadians participated in the labour market in September, compared to just 74 per cent in the United States.

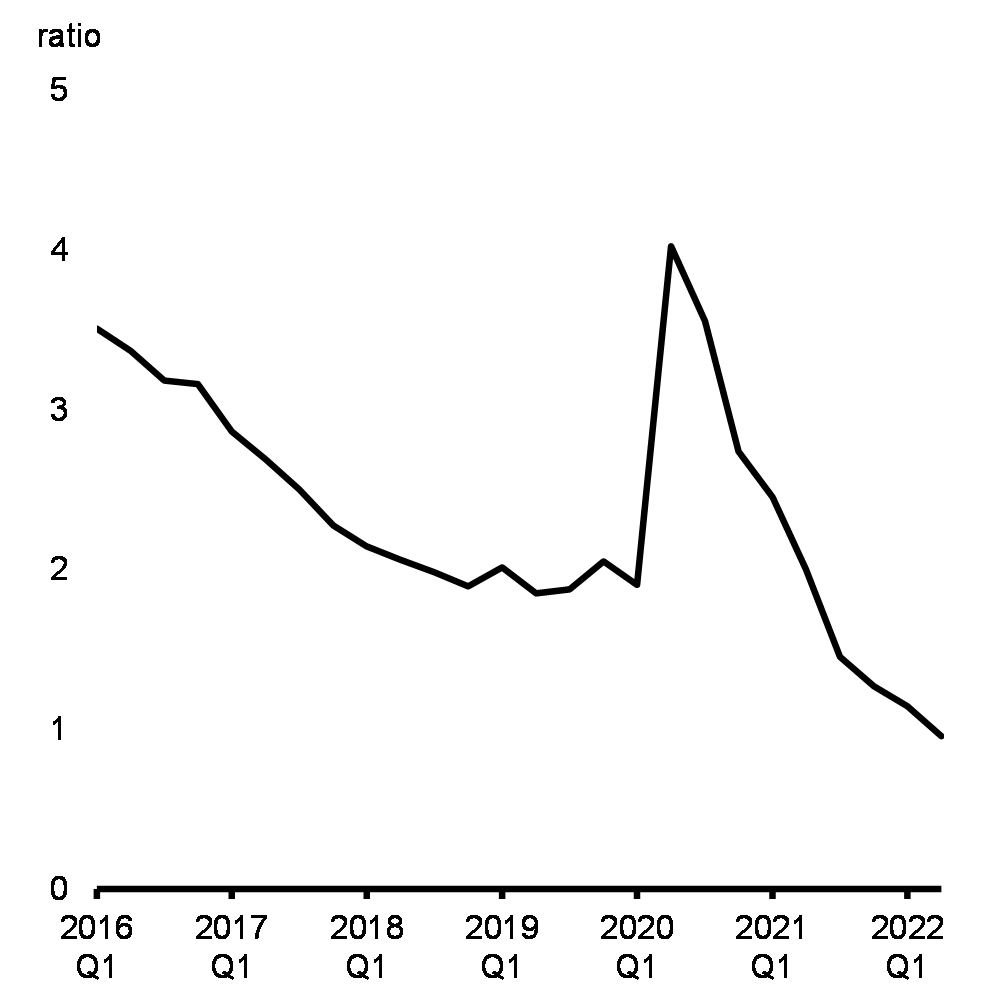

However, employers have struggled to fill available positions, partly fuelled by a shortfall in immigration earlier in the pandemic (Chart 1.13). Employers were seeking to fill over one million jobs in the second quarter, a record high, though the most timely data suggests some easing in labour demand. Canada’s strong employment recovery has reduced the number of available workers, limiting the potential for further sizeable job gains. This tightness in the labour market has also resulted in a solid rise in wage growth, which has helped lessen the impacts for some of the rising cost of living.

Unemployment Rate

Change in Employment Relative to Pre-Pandemic Level

A strong rebound in immigration has helped drive the recovery in population growth and the labour force. Canada has experienced the fastest population growth among G7 countries over the past several years (Chart 1.14). After declining sharply early in the pandemic, the number of new permanent residents in Canada surged by about 275,000 so far in 2022, with the government well on track to achieving its 2022 immigration target. Further, the numbers of students and temporary foreign workers also increased significantly. The economic benefits of immigration, which are in addition to the social and familial benefits, depend on how well newcomers integrate into the labour market. Canada is doing well in this regard as newcomers to Canada have steadily improved their labour force participation over the past few years. Canada continuing to be a destination of choice for those looking to build a better future for themselves and their families will be an important factor in our continued economic growth.

Job Searchers per Vacancy

Population Growth, G7 economies

Canada’s Economic Growth Has Slowed From Its Robust Pace

While Canada’s recovery has been solid, the economy is now showing signs of slowing and life has become more expensive for Canadians. Elevated inflation, combined with rising interest rates and lower equity prices, are weighing heavily on household finances and will slow household spending. At the same time, a weakening global economy is weighing on commodity prices and will ultimately have an impact on demand for Canadian exports. Overall, real GDP expanded by 1.8 per cent at an annual rate from May to August—a notable deceleration from a growth pace of 7.1 per cent between January and April.

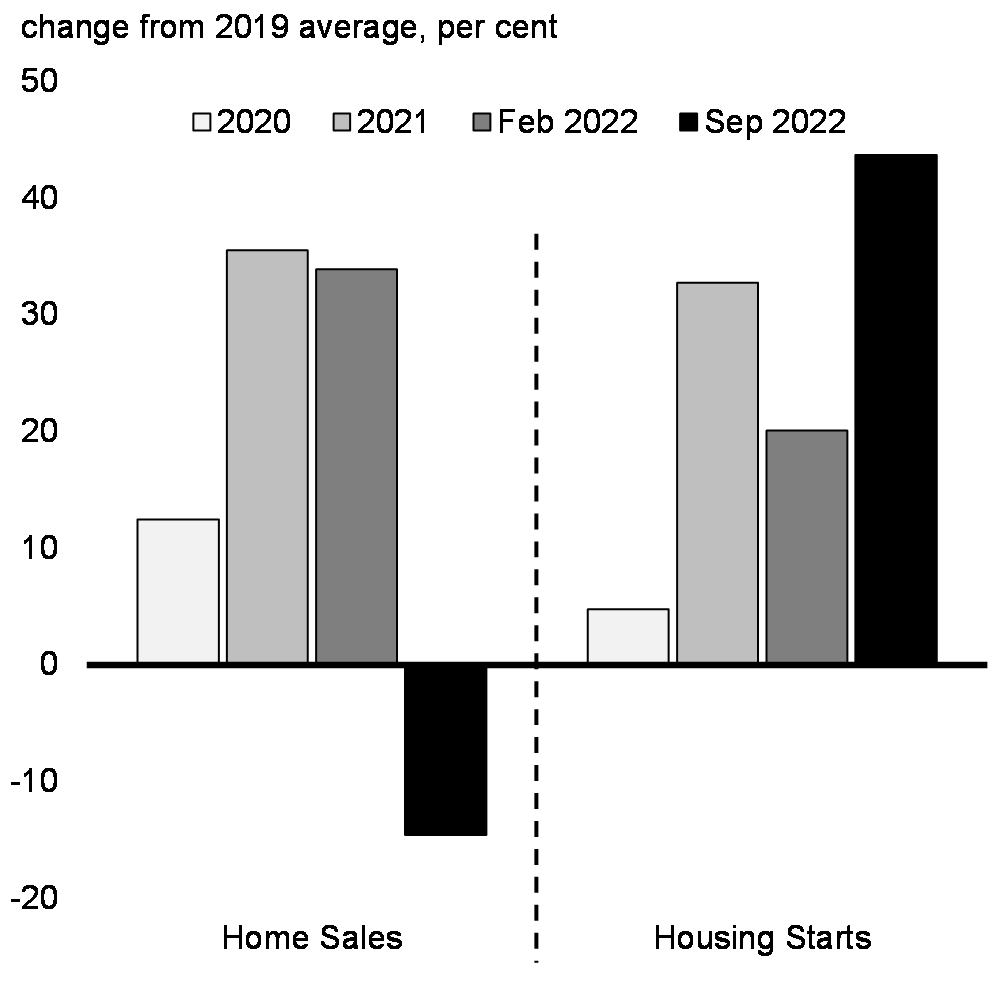

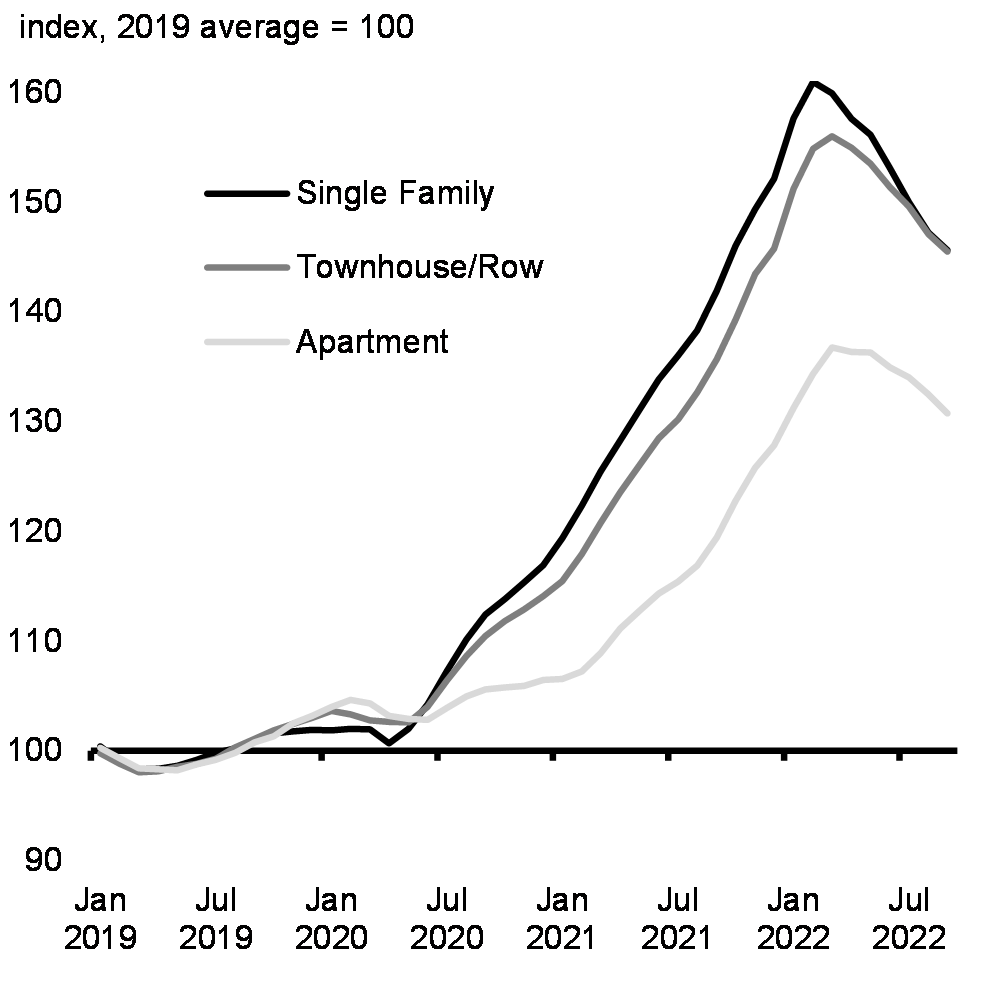

So far, the moderation in growth has been most evident in housing markets, which are undergoing a sharp pullback following unprecedented heights during the pandemic. Triggered by higher mortgage rates, resales are down 36 per cent from their peak in February, while house prices are down 9 per cent (Charts 1.15 and 1.16). The cooling in overheated house prices will help slow inflation and make it more affordable for Canadians to enter the housing market. Encouragingly, new construction has been quite resilient, which will also contribute to supply and help moderate housing prices.

Consumer spending, which surged earlier this year as public health restrictions were lifted, is also weakening. High inflation has increased the cost of virtually all goods and services. Bringing inflation under control is critical to ensuring working Canadians do not fall behind. Rising interest rates have raised the cost of borrowing over the past year, while falling home and equity prices have reduced household net worth. That said, there are some factors that may help buoy consumer spending. Notably, many households accumulated an unusually large amount of savings during the pandemic as people stayed home. Labour market conditions are also expected to remain solid.

Meanwhile, the global slowdown is beginning to impact Canadian exporters. The current moderation of commodity prices is weighing on export revenues and could reduce activity in commodity-producing sectors. The slowdown in global manufacturing activity will also drag on non-commodity exporters in the coming months. Despite a deterioration in global economic conditions, some factors could support exports and business investment as the global economy recovers through 2024. The rebound in international travel, the unwinding of global supply chain disruptions, and the recent depreciation of the Canadian dollar should partially offset the impact of weaker global activity on non-commodity exports. Capital expenditures could also increase in response to ongoing capacity constraints facing many businesses.

Key Measures of Housing Activity

Evolution of House Prices

1.2 Canadian Economic Outlook

The Department of Finance surveyed a group of private sector economists in early September 2022. The average of private sector forecasts has been used as the basis for economic and fiscal planning since 1994, helping to ensure objectivity and transparency, and introducing an element of independence into the government’s economic and fiscal forecast.

Since the private sector survey was conducted in early September, global economic and financial conditions have continued to deteriorate. While the macroeconomic inputs of the September survey continue to provide a reasonable basis for economic and fiscal planning (see Annex 1 for details of the economic and fiscal projections), the balance of risks to the growth outlook are tilted to the downside, with growth more likely to come in below the survey than above. To facilitate prudent economic and fiscal planning, the Department of Finance has developed an alternative scenario that illustrates a slower growth track relative to the September survey.

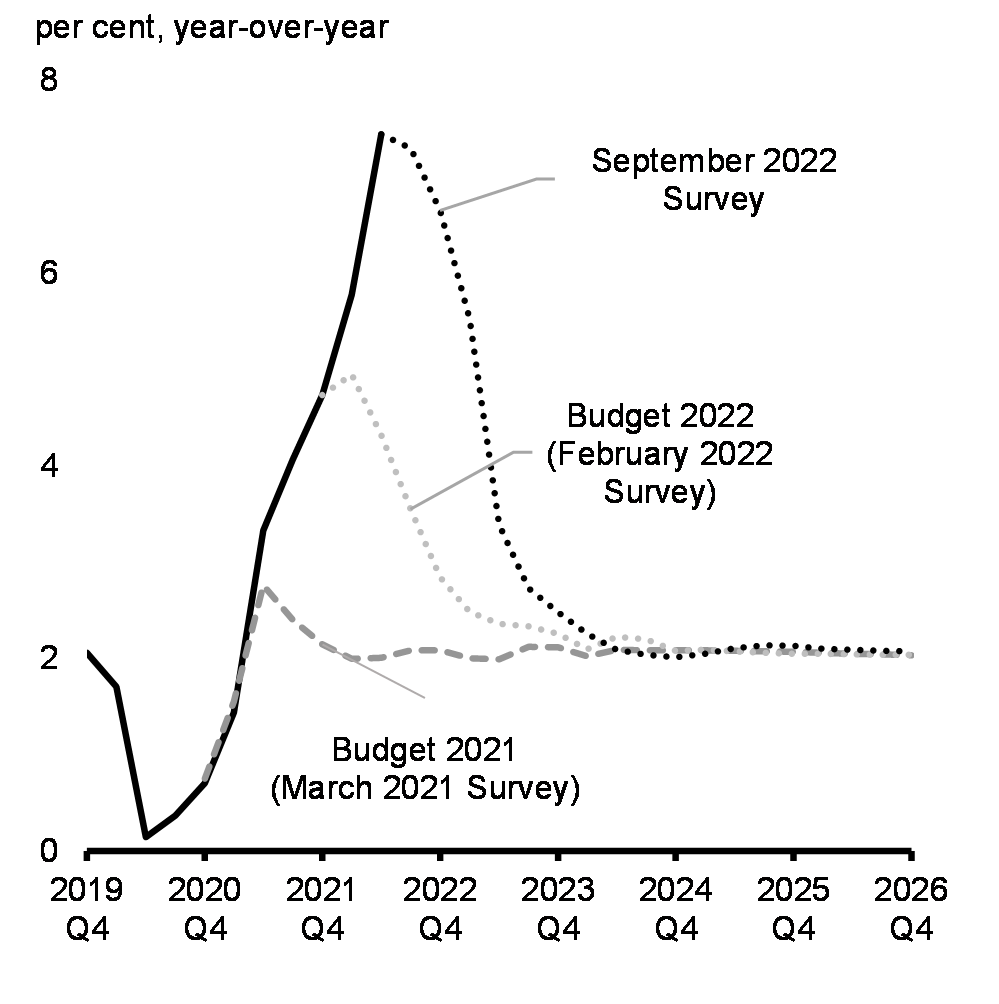

Private Sector Economists Expect Economic Growth to Slow Further

Inflation has been much higher than projected by private sector economists in Budget 2022, which was based on a survey conducted in early February 2022, before Russia’s illegal invasion of Ukraine. While private sector economists continue to believe Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation will return to the Bank of Canada’s target, this process is taking longer than previously expected. CPI inflation was projected to remain above 3 per cent until the third quarter of 2023—almost a year later than private sector economists predicted in Budget 2022—before reaching 2 per cent in mid-2024 (Chart 1.17).

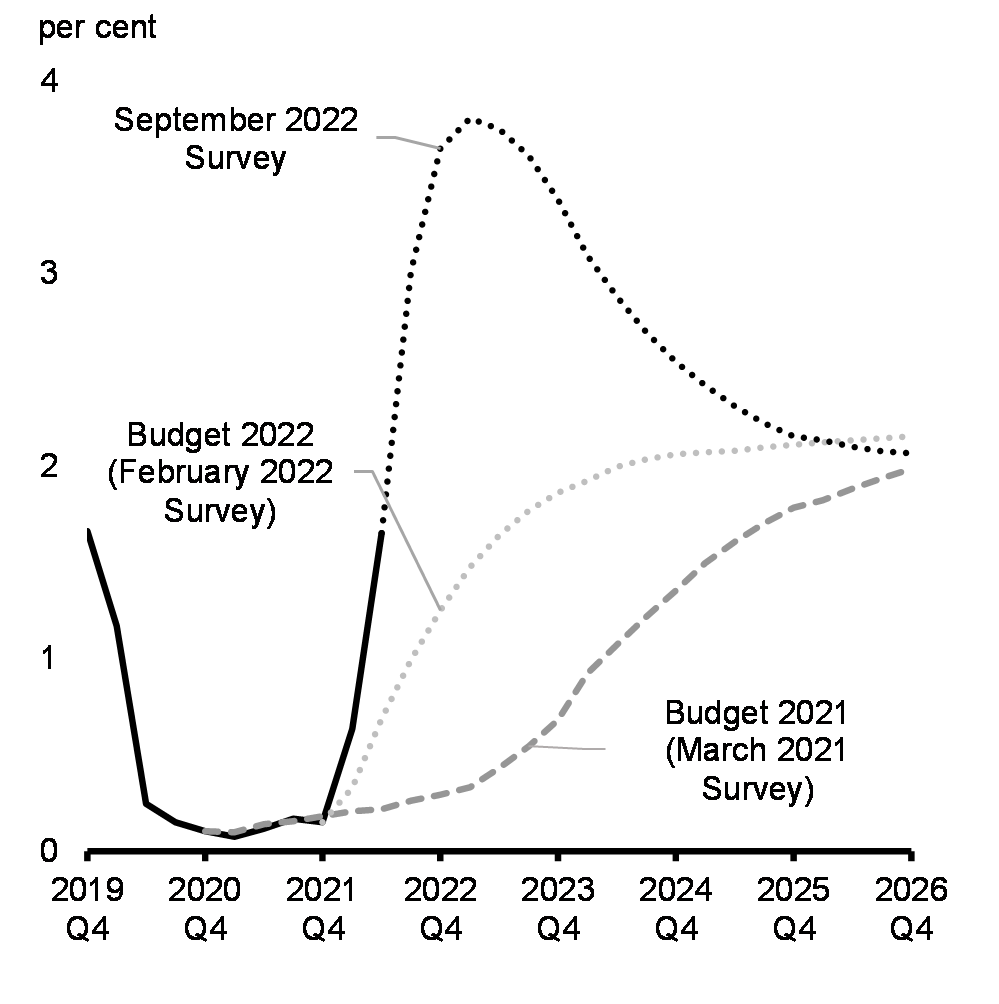

Persistent inflationary pressures have also led to a sharp increase in interest rates. At 3.0 per cent in the third quarter of 2022, short-term interest rates were roughly 200 basis point higher than expected by private sector economists in Budget 2022. Further ahead, private sector economists expected short-term interest rates to peak at 3.8 per cent in the first half of 2023 (Chart 1.18). This represents a substantial increase in the outlook for interest rates from that expected by private sector economists in Budget 2022.

Consumer Price Inflation Projections

Short-Term Interest Rate Projections

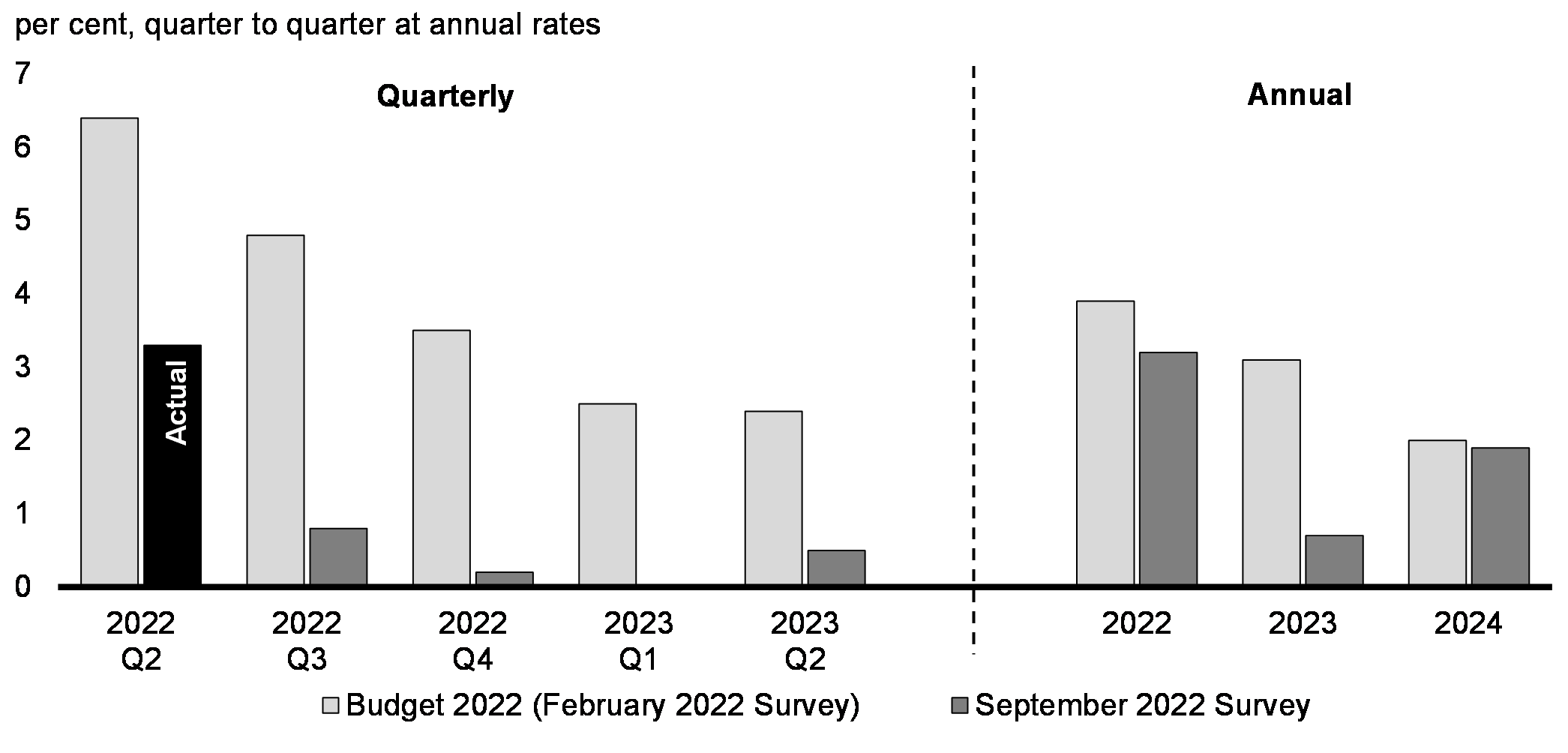

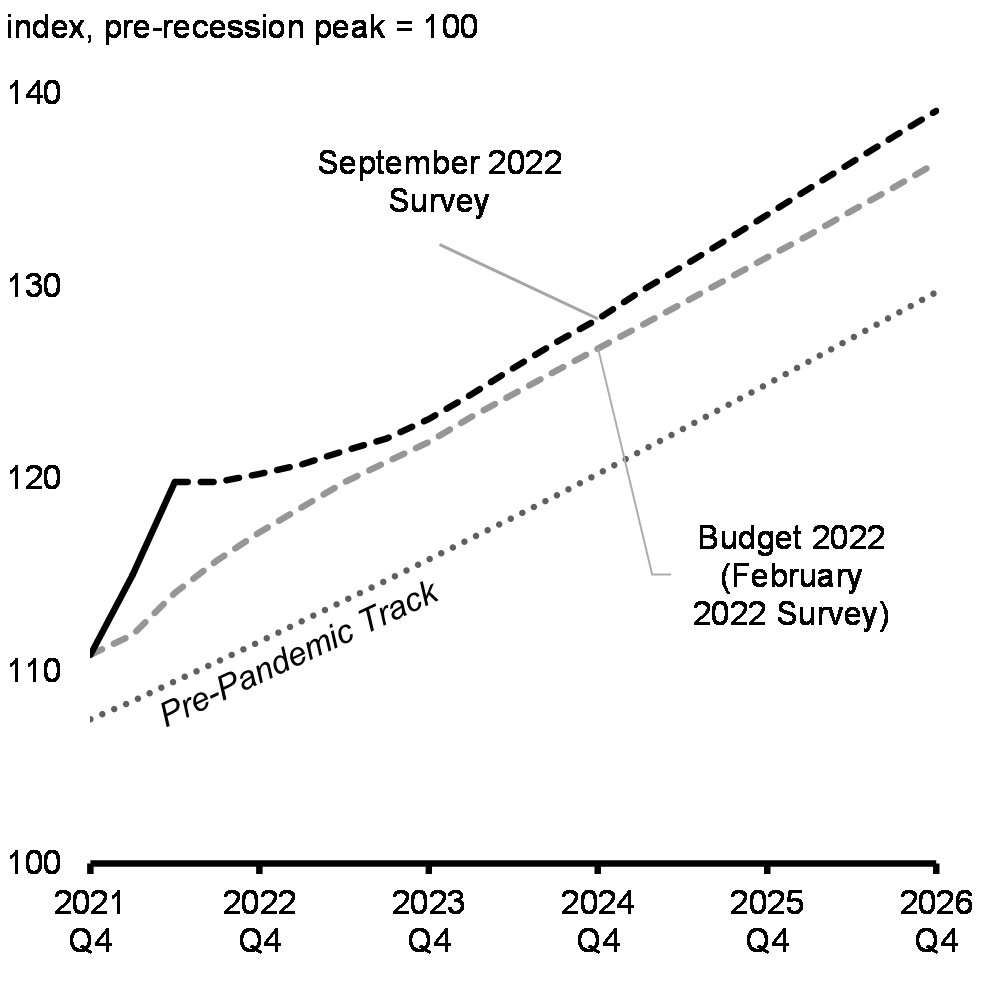

With higher inflation and interest rates, as well as slower economic growth in the United States and globally, private sector economists anticipated in their survey that Canada would see significantly weaker growth than anticipated in Budget 2022 (Chart1.19). Real GDP was projected to expand by a still strong 3.2 per cent in 2022 (from 3.9 per cent in Budget 2022) but growth was expected to slow to 0.7 per cent in 2023 (from 3.1 per cent). By the end of 2026, the level of real GDP was expected to remain about 2 per cent below Budget 2022 projections.

Overall, the September 2022 survey average indicates that the Canadian economy was expected to see a period of subdued growth. Real GDP growth was projected to be just above zero for the next several quarters. As a result, the unemployment rate was expected to increase from the current rate of 5.2 per cent to 6.3 per cent by the end of 2023—above Budget 2022 projections (5.5 per cent) but low by historical standards. The unemployment rate was then expected to decline to 5.7 per cent by the end of the forecast horizon.

Real GDP Growth Projections

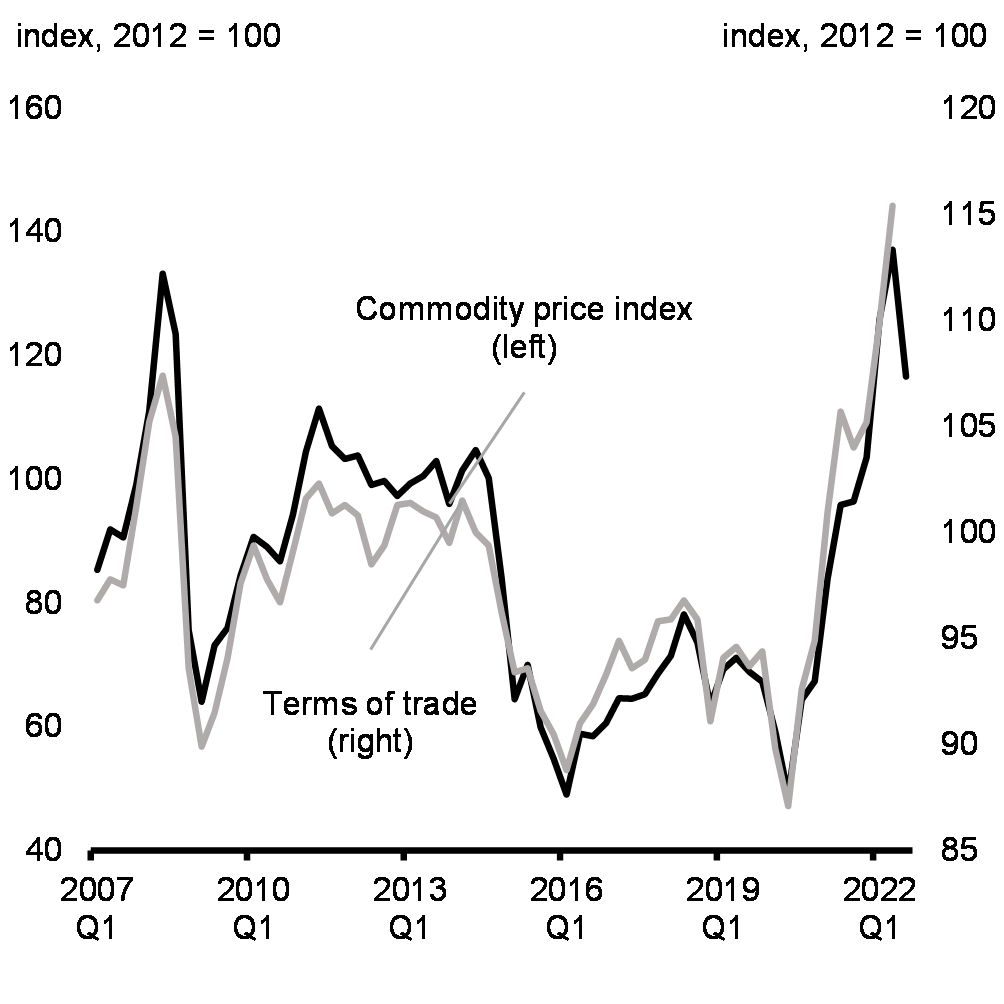

Despite lower growth prospects since Budget 2022, the Canadian economy has seen a significant boost to national income from higher commodity prices following Russia’s illegal invasion of Ukraine. Higher prices for a range of commodities that Canada exports pushed up our terms of trade (the ratio of export prices to import prices) to an all-time high in the second quarter of 2022 (Chart 1.20). Higher export prices have, in turn, boosted the revenues of Canadian exporters, corporate profits, and GDP inflation (a measure of price changes for all of the goods and services produced in the economy). These trends have been widespread across sectors and regions of Canada, supporting revenues of all orders of government, including provinces and territories.

As a result, the projected level of nominal GDP (the broadest measure of the tax base) in the September survey is $94 billion above Budget 2022 expectations for 2022 (Chart 1.21). However, with a reduced outlook for real GDP growth in 2023, the boost to nominal GDP was expected to partly unwind next year, leaving the projected level of nominal GDP up by an average of $54 billion per year over the entire forecast horizon relative to Budget 2022 projections.

Terms of Trade and Commodity Prices

Nominal GDP Projections

Increasing Probability of a More Pronounced Slowdown

At the time of the September 2022 survey, most private sector economists continued to expect that Canada would avoid a “hard landing”—that is, inflation will moderate without a recession. This growth outlook is subject to significant downside risks. Primarily, this relates to the path of inflation. How quickly inflation moderates will determine how high interest rates will rise and how long they remain elevated, and therefore how sharply global activity will cool. A more pronounced slowdown, both in Canada and globally, is possible if high inflation becomes more deeply entrenched.

Even without a further upward drift in inflation, several factors are contributing to the risk of an unexpectedly steep downturn in global activity:

- There is considerable uncertainty about the impacts of the unusually sharp and synchronous global monetary policy tightening;

- The European energy crisis could further unsettle commodity markets;

- The Chinese property market slowdown could disrupt financial markets; and

- In Canada, the economy could turn out to be more sensitive to higher interest rates than anticipated. This is most likely to manifest as a sharper correction in the housing market.

In addition, since the survey was conducted in early September, global economic and financial conditions have continued to deteriorate. At the time of the survey, forecasters attached a roughly 40 per cent probability to a recession in 2023. Since then, the U.S. Federal Reserve’s more aggressive posture on inflation has led to a substantial shift in sentiment that has caused widespread volatility in financial markets. There have also been further signs that the global economy is slowing more quickly than anticipated. All of this suggests that since the survey was completed, the trajectory of the global economy has led to increasing uncertainty about how much growth in Canada will slow.

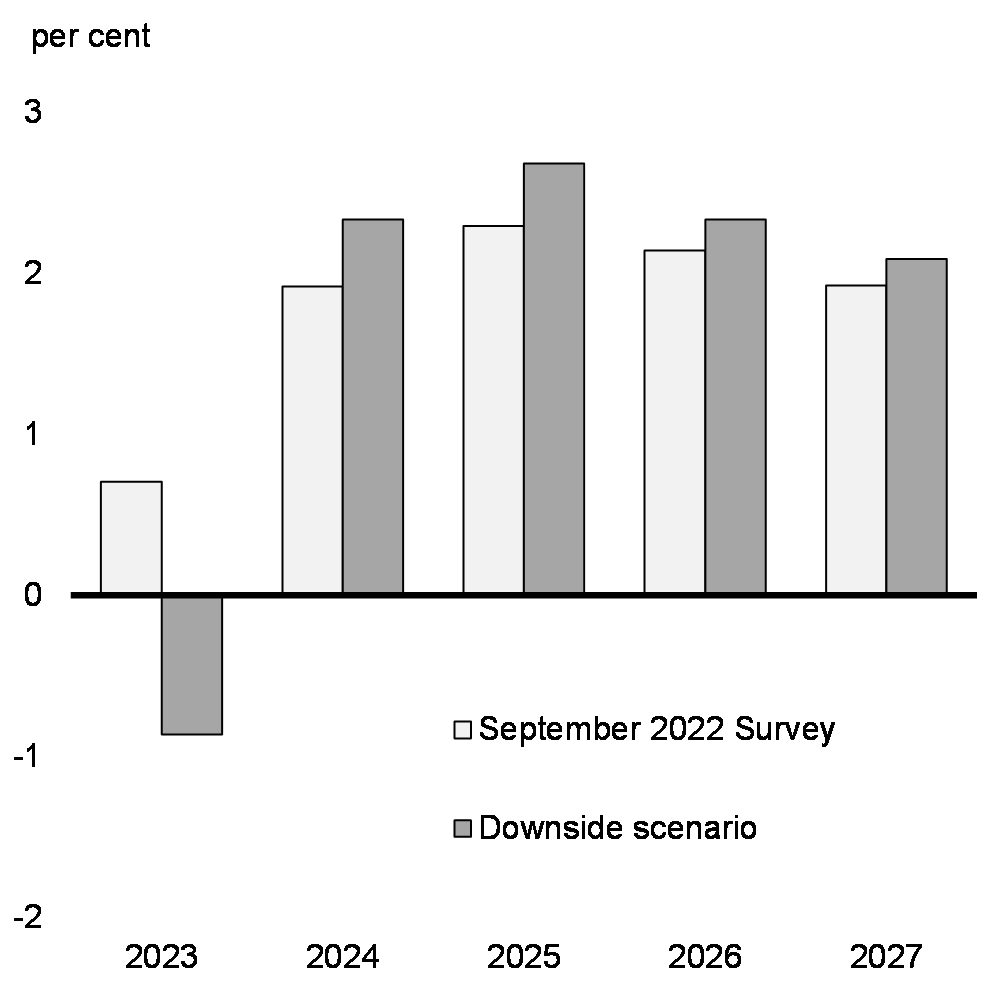

Overall, the macroeconomic inputs of the September survey continue to provide a reasonable basis for economic and fiscal planning (see Annex 1 for details of the economic and fiscal projections). However, in light of recent developments and the significant downside risks to the near-term growth outlook, the Department of Finance has developed a downside scenario that considers the impact of more persistent inflationary pressures and further tightening in monetary policy, leading to a “hard landing” in the economy. In this scenario, elevated inflation becomes more deeply entrenched, particularly in the U.S., leading central banks to raise interest rates by more than anticipated to return inflation to target. This increases long-term interest rates and leads to a significant tightening in global financial conditions. Tighter financial conditions result in more adverse effects on confidence, wealth and activity, resulting in a sharper correction in housing markets and consumer activity in Canada, as well as larger spillovers from tightening and weaker economic activity in other countries.

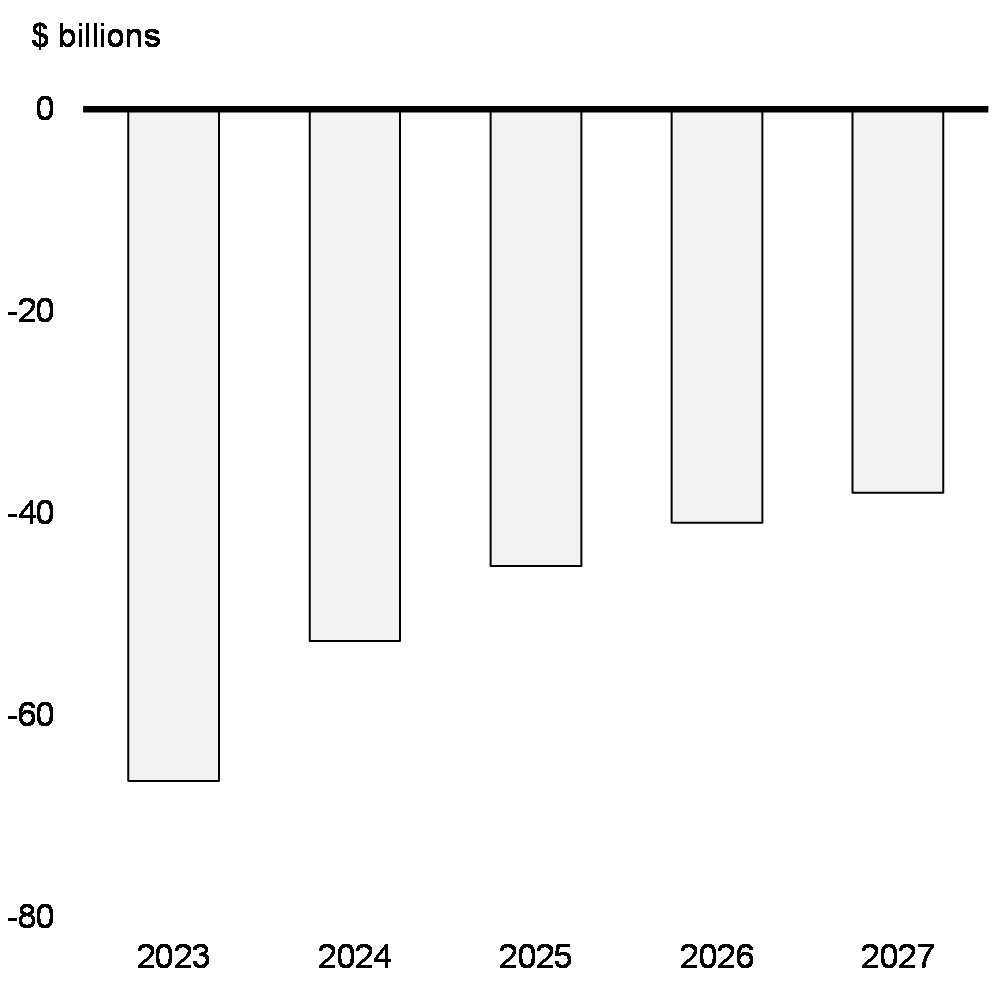

In the downside scenario, CPI inflation is 1.8 percentage points above the September 2022 survey in 2023, and stays above 3 per cent until the first quarter of 2024—about six months longer than in the survey—before reaching 2 per cent by the end of 2024. In response, short-term interest rates reach 4.5 per cent in the first half of 2023 and are up by 0.7 percentage points over the entire forecast horizon. As a result, Canada enters a mild recession in the first quarter of 2023. Real GDP contracts by 1.6 per cent from peak to trough, well below the 4.4-per-cent contraction in 2008-09. Similarly, the unemployment rate rises 1.7 percentage points to 6.9 per cent in the second half of 2023, far lower than the peak of 8.7 per cent experienced following the 2008-09 contraction. For 2023 as a whole, real GDP declines by 0.9 per cent and the unemployment rate is 0.5 percentage point above the survey. At the same time, weaker global demand weighs on commodity prices, with oil prices US$8 per barrel below the survey in 2023. Despite higher CPI inflation, lower commodity prices lead to lower GDP inflation and, combined with slower growth, result in a level of nominal GDP that is $45 billion lower than the survey, on average.

Real GDP Growth

Nominal GDP Level Difference Between the Downside Scenario and the September 2022 Survey

1.3 Investing to Expand the Supply Capacity of the Economy

Recent events have demonstrated how sensitive the global economy can be to sudden changes in supply. While these disruptions are the outcomes of an extreme set of circumstances, moving forward, the global economy is likely to be shaped by trends that will create a drag on productive capacity and increase the frequency of supply chain disruptions.

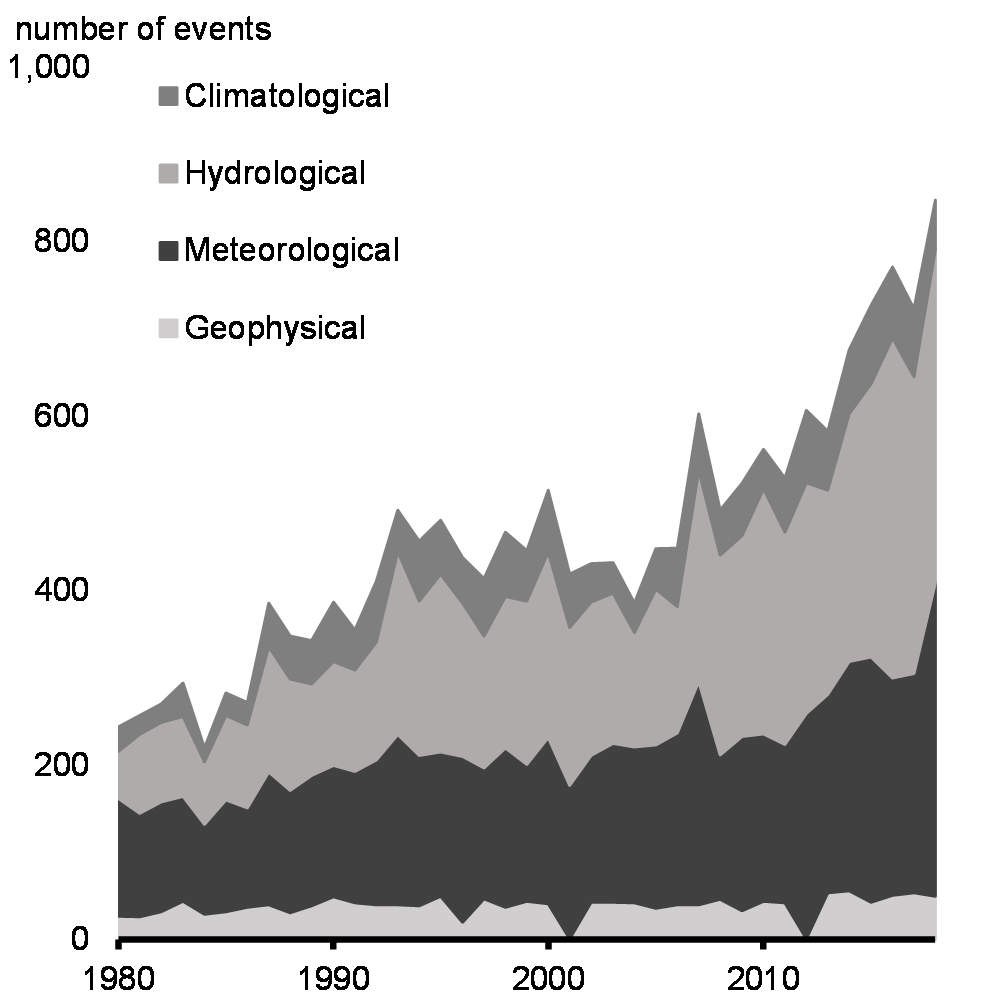

Climate change will increase the frequency of extreme weather and natural disasters (Chart 1.24). Rising geopolitical tensions have the potential to lead to more frequent disruption of trading relationships and more volatile prices for commodities.

Domestically, population aging will make it harder for businesses to recruit workers. While harnessing demand for Canadian products and expertise in a net-zero world will create jobs and build a competitive Canadian economy, careful work must be done to support workers and businesses during this transition.

There is uncertainty about how each of these trends will unfold, but they all point to supply remaining an important constraint over the longer term.

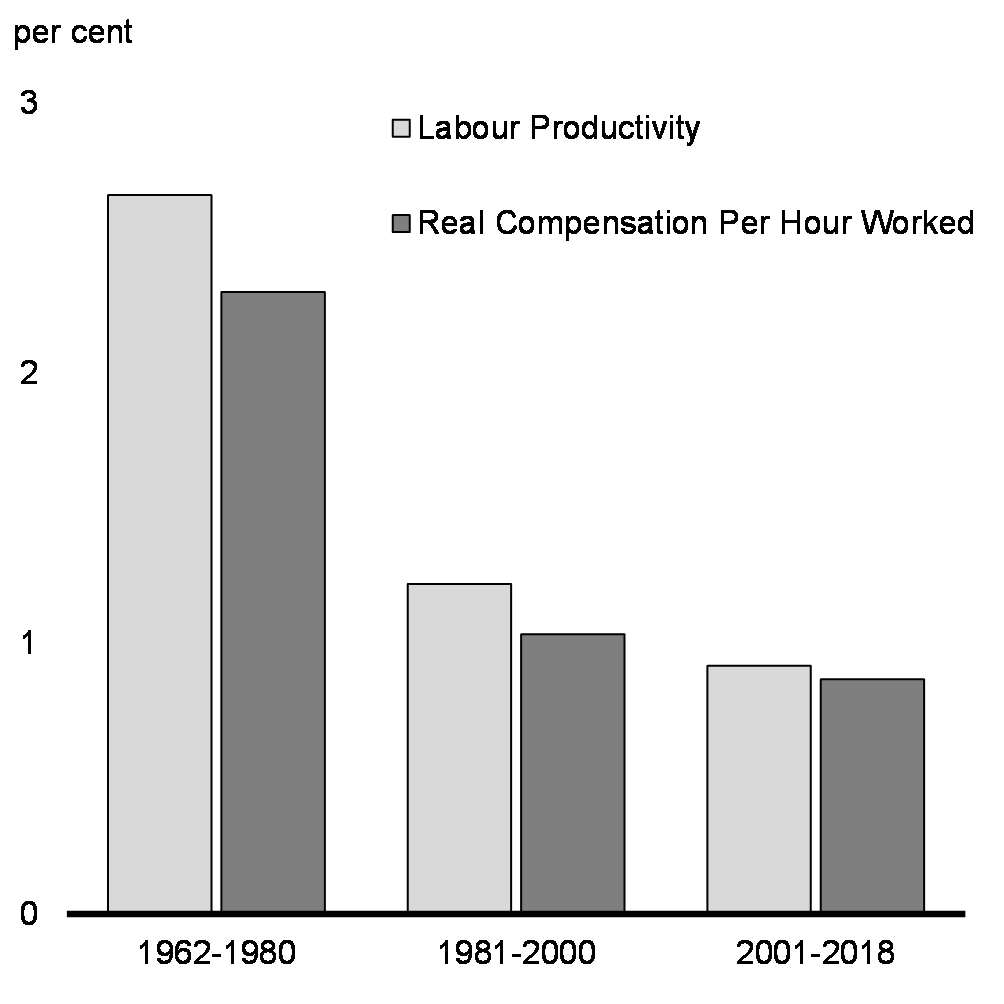

In the long run, Canadians’ ongoing prosperity and quality of life will depend on expanding the supply capacity of the economy to achieve robust growth. To do this, we will have to grow our workforce, ensure that workers have the skills they need for a changing global economy, and invest in helping businesses grow and create good jobs for Canadians. (Chart 1.25).

Rising Natural Disaster Events Worldwide

Canadian Labour Productivity and Real Labour Compensation Rate Growth

Canada Must Boost Investment

Canada faces the future with many strengths—a highly educated population, a way of life and society that attracts people from around the world, and abundant natural resources. But Canada will require capital to finance the enormous investments needed to meet the challenges ahead.

In Canada, the transition to a net-zero economy will require significant investment from both governments and the private sector. Investments will also be needed to limit strategic vulnerabilities in supply chains. Smart investments in areas like critical minerals, energy, agriculture, and electric vehicles are needed to help make Canada a leader in the clean and digital technologies that the world counts on. Likewise, education, training, and skills development will be crucial to ensure that Canadians thrive in a changing economy. In light of the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act, significant steps will need to be taken to ensure that Canada remains competitive in North America and the world.

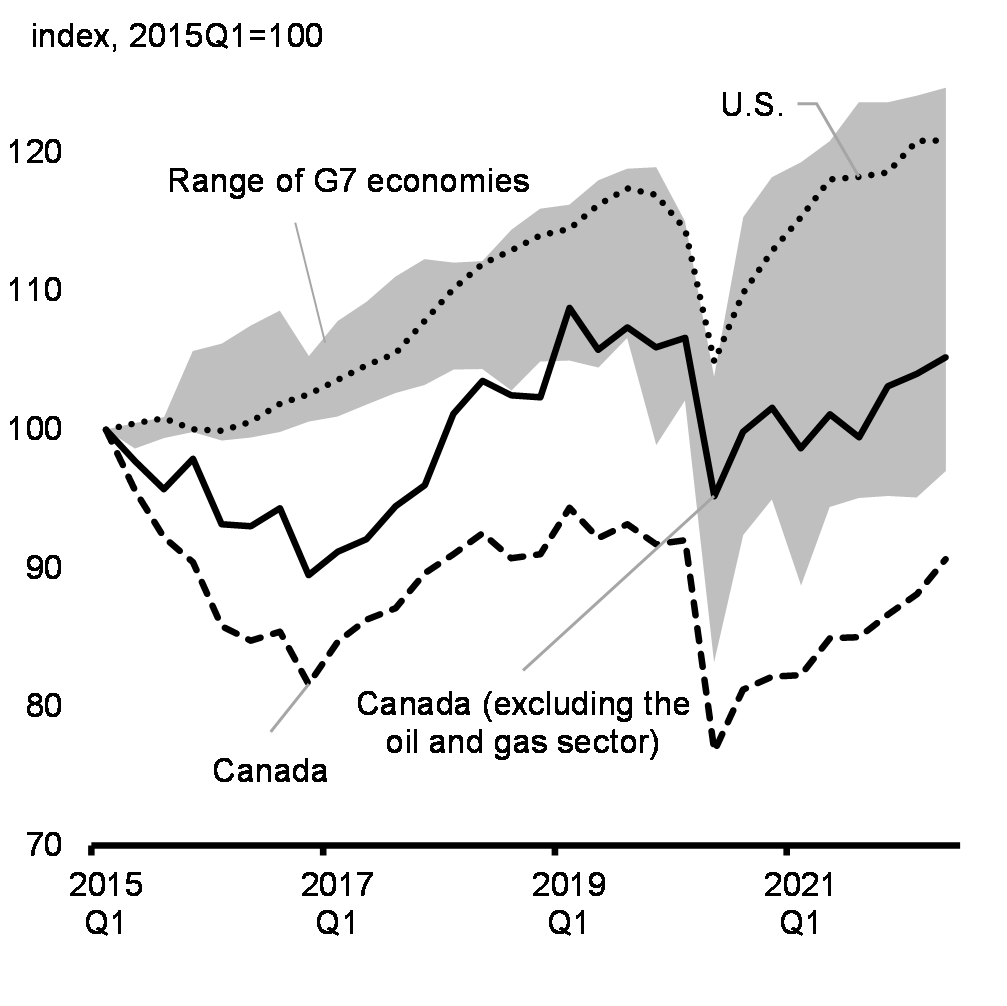

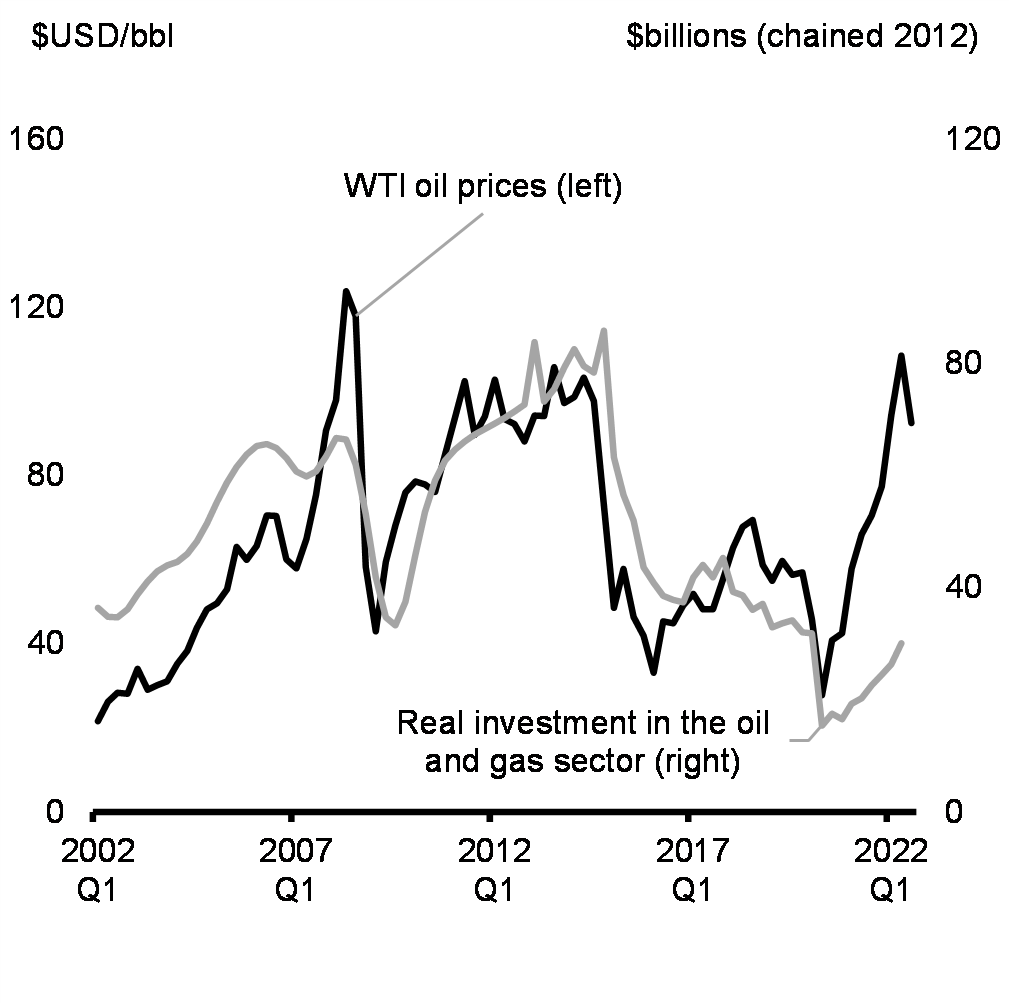

In the past, strong investment in the oil and gas sector compensated for weakness in other segments of the economy. As the world moves towards net-zero, global investment growth in that sector has declined, and the historical weakness of business investment in Canada has become more apparent (Chart 1.26). Canadian firms have invested in information and communication technology (ICT) at only half the rate of their U.S. counterparts. Likewise, research and development intensity has steadily fallen over the last two decades, to a level roughly one third that of the U.S. These types of investments drive productivity growth and are essential for equipping Canadian workers to succeed in the economy of the future. While some new investments have been made by leading businesses across the Canadian economy in the past 12 months, investment remains 1.2 per cent below its pre-pandemic level. Notably, investment in the oil and gas sector remains muted despite the sharp rise in oil prices following the illegal Russian invasion of Ukraine (Chart 1.27). This weakness in business investment has also been reflected in the performance of foreign direct investment (FDI) in new capital projects, the types of so-called greenfield investments that contribute to Canada’s productive capacity. Reversing this historical trend is an urgent priority for the government, as evidenced by significant investments in Budget 2022 and in the 2022 Fall Economic Statement.

Real Business Investment Since 2015 in Canada, the United States and G7 Economies

Real Investment in the Oil and Gas Sector and Oil Prices

Strengthening Canada’s economic prospects will depend on the government continually working to attract skilled immigrants and increase labour force participation, continuing to invest in education and training, making productivity-improving investments in infrastructure, and creating the conditions for Canada to attract further investment—both domestic and international.

Government can play an important role in spurring these types of investments and growing Canada’s productive capacity, while also reducing emissions and fighting climate change. However, government actions must strike the right balance between promoting the investments needed for Canada’s long-term prosperity and ensuring that it does not amplify inflation in a way that would make it harder for Canadians to keep up with the cost of living. Building on the measures from Budget 2022, the government will ensure that new investments are balanced and targeted to enhance Canada’s productive capacity,create good-paying jobs, and build an economy that works for everyone.

1.4 Fiscal Outlook

A Responsible Fiscal Plan

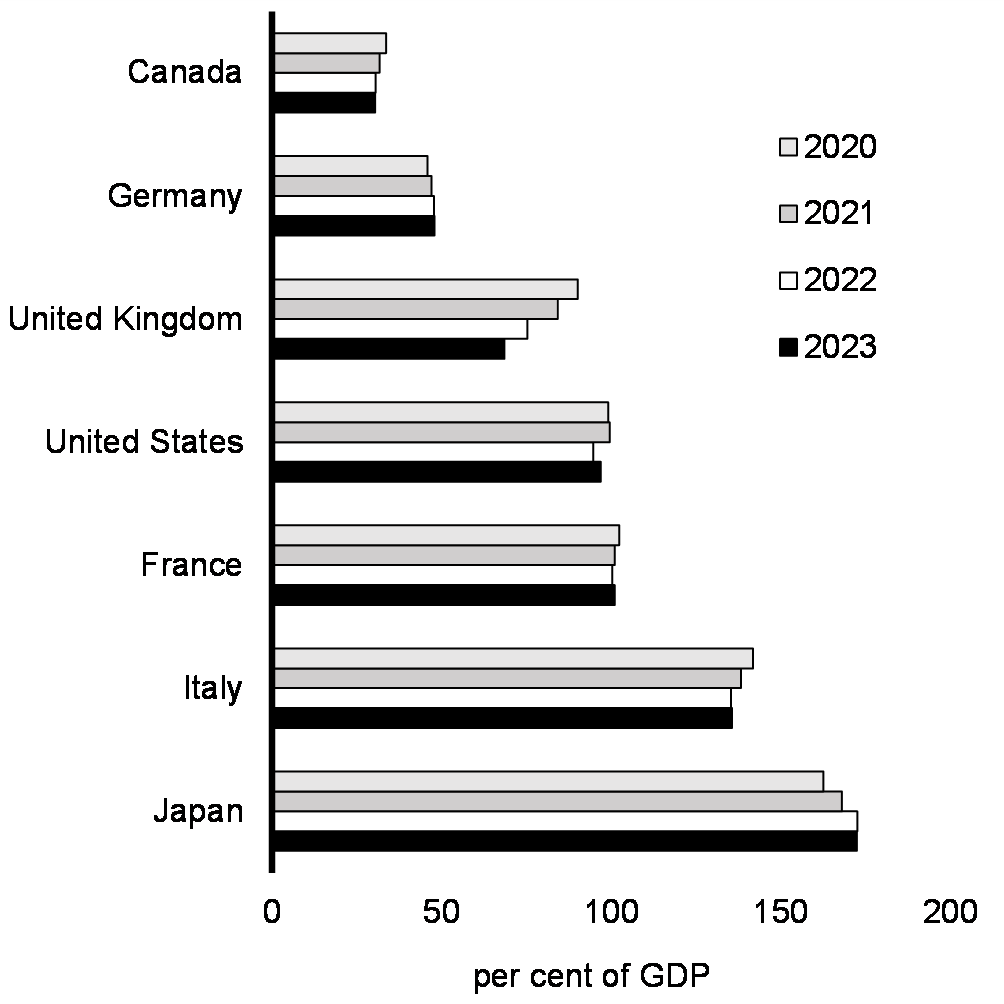

Since 2015, the government has demonstrated that it can responsibly support Canadians while also investing in people and the long-term capacity of Canada’s economy. As we emerge from the pandemic, the government is running a tighter fiscal ship. Canada has an enviable position amongst its peers, with the lowest net debt and deficit as a share of the economy in the G7. Given current economic conditions, continuing fiscal prudence will be important to ensure that inflation is not made worse or longer lasting, while also ensuring the government retains the fiscal capacity to provide targeted support to Canadians, if required.

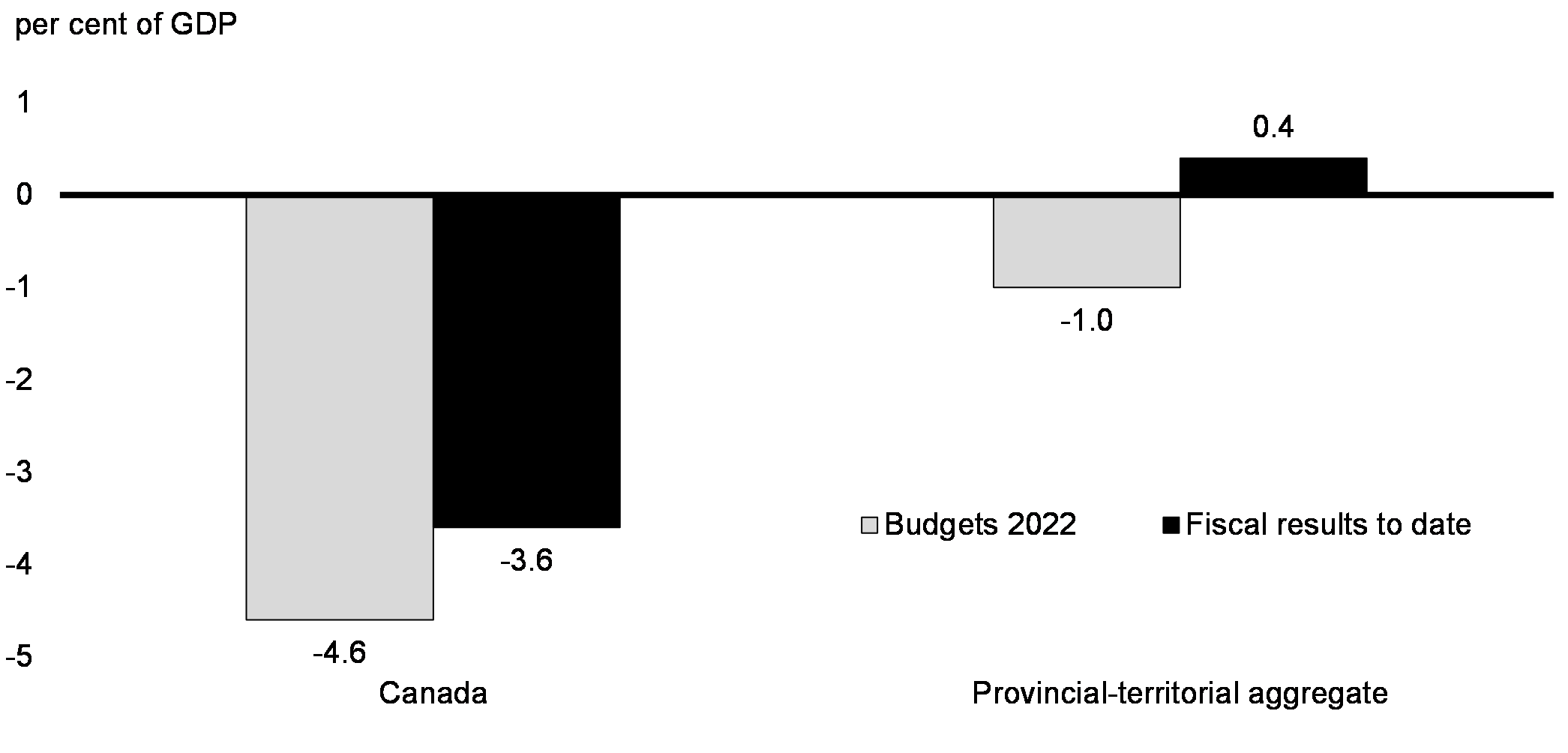

Provincial and territorial governments continue to significantly outperform fiscal projections. Fiscal results to date show that the aggregate provincial-territorial budgetary balances moved into a surplus position in 2021-22, as opposed to the 1 per cent of GDP deficit that had been expected at the time of 2022 budgets. The improvement in provincial-territorial budgets was in line with, but somewhat larger than, the better-than-expected result at the federal level of a deficit of 3.6 per cent of GDP (Chart 1.28).

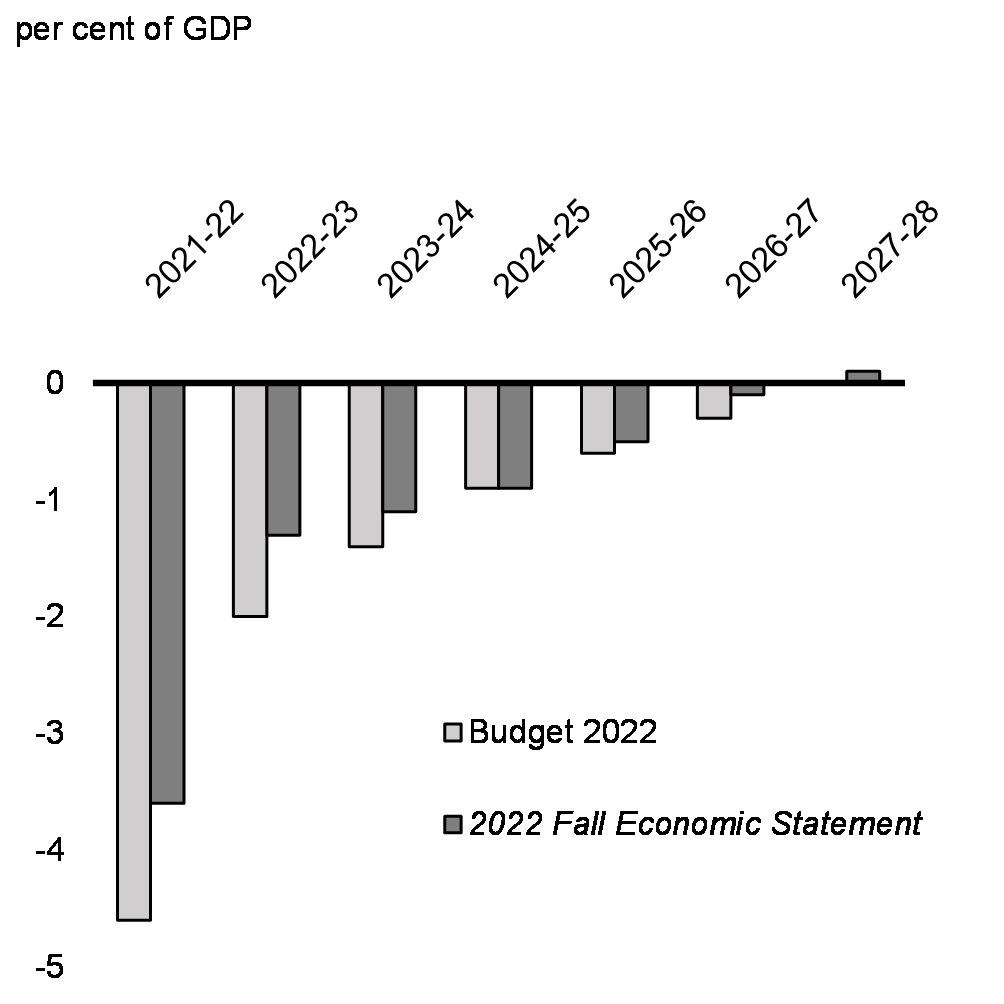

2021-22 Budgetary Balances

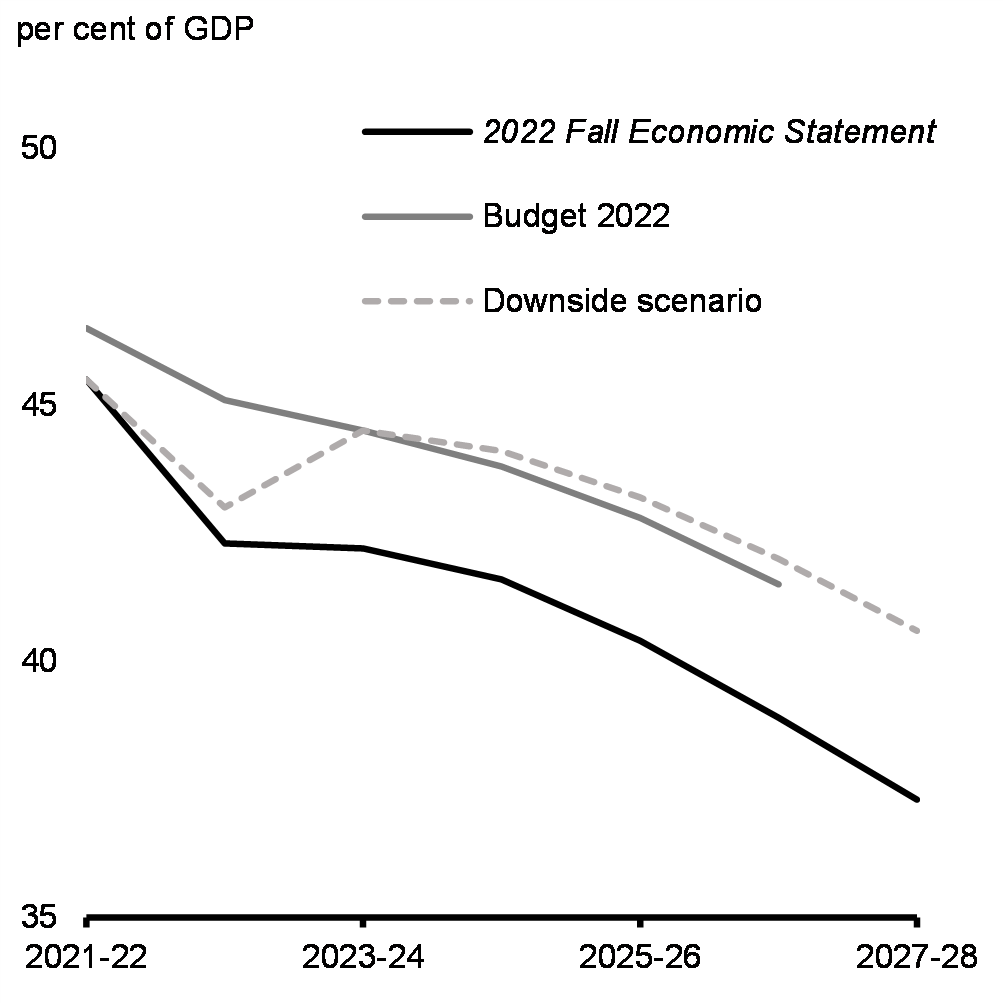

After accounting for better-than-expected fiscal results, measures in the 2022 Fall Economic Statement and other new policy actions since Budget 2022, and incorporating the results of the September 2022 survey of private sector economists, the budgetary balance is expected to remain below the $52.8 billion deficit projected in Budget 2022, with a $36.4 billion expected deficit in 2022-23, about -1.3 per cent of GDP, improving to a $4.5 billion surplus in 2027-28, or about 0.1 per cent of GDP (Table 1). Looking out over the next five years, the federal deficit (Chart 1.29) and federal debt (Chart 1.30) as a share of the economy are projected to be reduced each year and remain well below the Budget 2022 forecast.

The responsible approach outlined in this chapter builds on the plan outlined in Budget 2022 to ensure that the federal government can respond to the challenges that may face Canadians in the coming year—both those that are anticipated and those that remain unknown. The federal government made use of its accumulated fiscal firepower during the global pandemic to help Canadians stay safe and avoid many of the devastating consequences we witnessed elsewhere in the world. In the face of economic headwinds, Canadians should have the confidence that the government is able to deliver timely and effective support to families and communities, and build an economy that works for everyone.

By maintaining our fiscal firepower, the government is ensuring that it will have the capacity to act if needed. That capacity to act in the near future, when combined with the measures introduced elsewhere in the 2022 Fall Economic Statement to help with affordability challenges, is at the heart of the government’s commitment to stand in support of all Canadians as we face the challenges of this unprecedented time together.

| Projection | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021– 2022 |

2022– 2023 |

2023– 2024 |

2024– 2025 |

2025– 2026 |

2026– 2027 |

2027– 2028 |

|

| Budgetary balance – Budget 2022 | -113.8 | -52.8 | -39.9 | -27.8 | -18.6 | -8.4 | |

| Impact of September private sector survey and other fiscal developments | 23.6 | 29.8 | 18.8 | 11.0 | 10.2 | 11.4 | |

| Budgetary balance before policy actions and measures | -90.2 | -23.0 | -21.1 | -16.8 | -8.4 | 3.0 | 12.8 |

| Policy actions since Budget 2022 | -7.3 | -4.3 | -2.9 | -1.8 | -1.8 | -3.5 | |

| 2022 Fall Economic Statement measures (by chapter) | |||||||

|

Making Life More Affordable

|

-4.4 | -1.3 | -1.3 | -1.3 | -1.4 | -1.4 | |

|

Jobs, Growth, and an Economy That Works for Everyone

|

-0.1 | -2.1 | -2.3 | -1.8 | -2.3 | -2.4 | |

|

Fair and Effective Government

|

-0.6 | -0.8 | -0.2 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.6 | |

|

Provision for anticipated near-term pressures1

|

-1.0 | -1.0 | -2.0 | -1.5 | -1.5 | -1.5 | |

| Total – 2022 Fall Economic Statement measures | -6.1 | -5.2 | -5.8 | -4.2 | -4.6 | -4.7 | |

| Budgetary Balance – Baseline Scenario | -90.2 | -36.4 | -30.6 | -25.4 | -14.5 | -3.4 | 4.5 |

| Fiscal impact of downside economic scenario | -12.7 | -21.8 | -16.8 | -15.9 | -15.3 | -12.8 | |

| Budgetary Balance – Downside Scenario | -90.2 | -49.1 | -52.4 | -42.3 | -30.4 | -18.6 | -8.3 |

| Baseline Scenario | |||||||

| Budgetary Balance (per cent of GDP) | -3.6 | -1.3 | -1.1 | -0.9 | -0.5 | -0.1 | 0.1 |

| Federal Debt (per cent of GDP) | 45.5 | 42.3 | 42.2 | 41.6 | 40.4 | 38.9 | 37.3 |

| Downside Scenario | |||||||

| Budgetary Balance (per cent of GDP) | -3.6 | -1.8 | -1.9 | -1.5 | -1.0 | -0.6 | -0.3 |

| Federal Debt (per cent of GDP) | 45.5 | 43.0 | 44.5 | 44.1 | 43.2 | 42.0 | 40.6 |

| Budget 2022 Projections | |||||||

| Budgetary Balance (per cent of GDP) | -4.6 | -2.0 | -1.4 | -0.9 | -0.6 | -0.3 | |

| Federal Debt (per cent of GDP) | 46.5 | 45.1 | 44.5 | 43.8 | 42.8 | 41.5 | |

|

Note: Totals may not add due to rounding. 1 Provision of $8.5 billion over six years, for pressures that are expected to materialize in the near term. |

|||||||

Budgetary Balance

Federal Debt

Downside Scenario

In the downside scenario (as presented in Section 1.2), the budgetary balance would deteriorate by an average of approximately $16 billion per year and add 3.3 percentage points to the federal debt-to-GDP ratio by 2027-28 (Chart 1.30). The higher deficits under the downside scenario are driven by:

- A reduction in projected tax revenues, led by corporate and personal income tax revenues, due to the lower outlook for nominal GDP, which would result in lower corporate profits and personal incomes.

- Higher expected program expenses as the higher unemployment rate would raise Employment Insurance benefit expenses, while higher CPI inflation would raise the cost of inflation-indexed programs such as seniors benefits and the Canada Child Benefit, and;

- Increased public debt charges as higher interest rates would lead to higher interest payments on the government’s interest bearing debt.

That said, even under the downside scenario, the federal debt-to-GDP ratio would still be on a downward trend over the medium term and be lower in 2027-28 than it is today. Details of the government’s fiscal outlook and the fiscal impact of the downside scenario can be found in Annex 1.

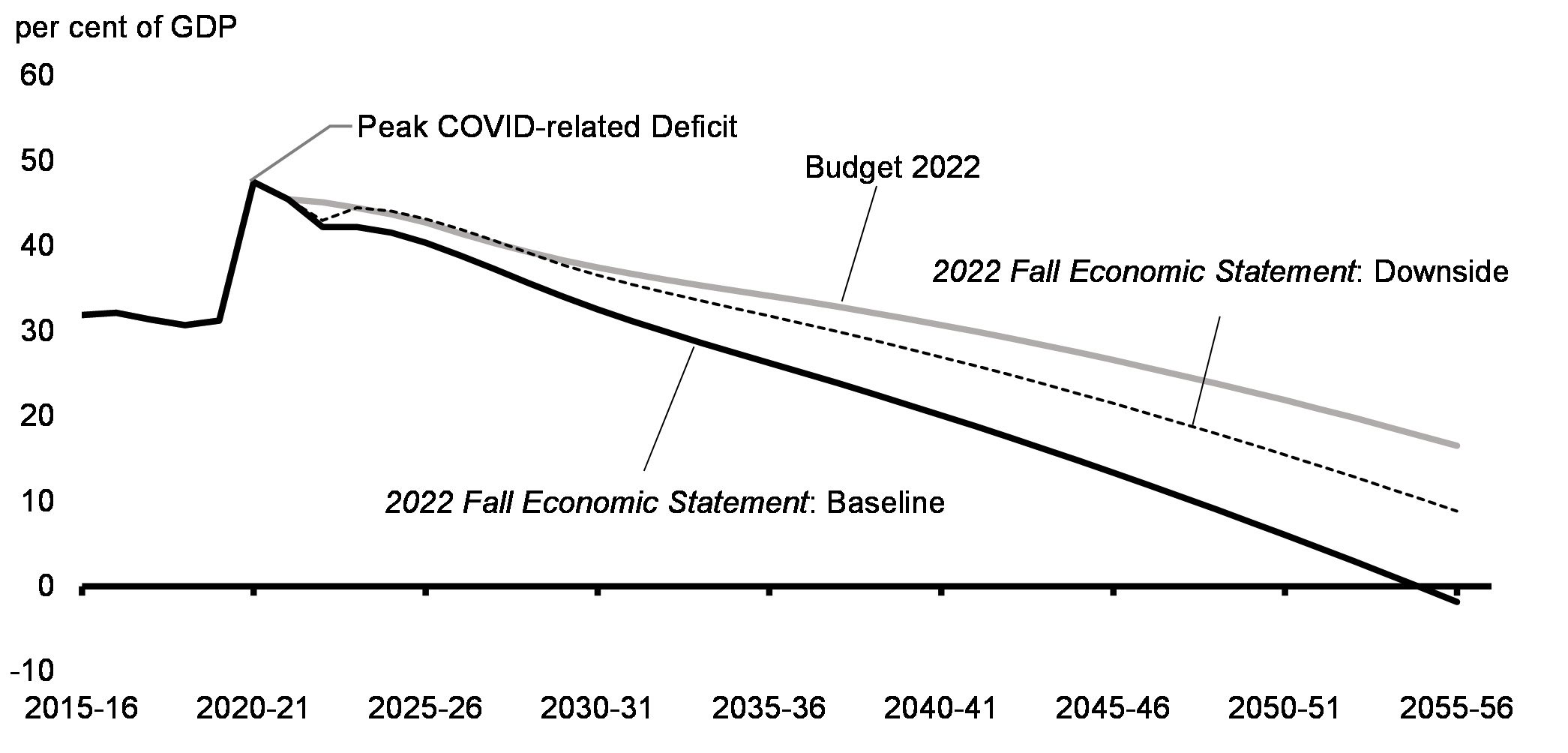

The Fiscal Anchor

The federal government’s fiscal anchor—the unwinding of COVID-19-related deficits and reducing the federal debt-to-GDP ratio over the medium term—remains unchanged and is being acted upon.

This fiscal anchor is helping and will continue to help ensure Canada’s low-debt advantage and enviable credit ratings are preserved, and that future generations have the fiscal capacity necessary to respond to the challenges they will face.

Considering the government’s fiscal anchor and using the 2022 Fall Economic Statement forecasts as a starting point, the government’s plan is fiscally sustainable over the long term. Over the next three decades, the federal debt-to-GDP ratio is projected to continuously decline and be on a steeper downward track than projected in Budget 2022 (Chart 1.31). Sensitivity analysis around these long-term fiscal projections also suggests fiscal sustainability would be preserved under the downside scenario (see Annex 1 for details).

Long-Term Projection of the Federal Debt

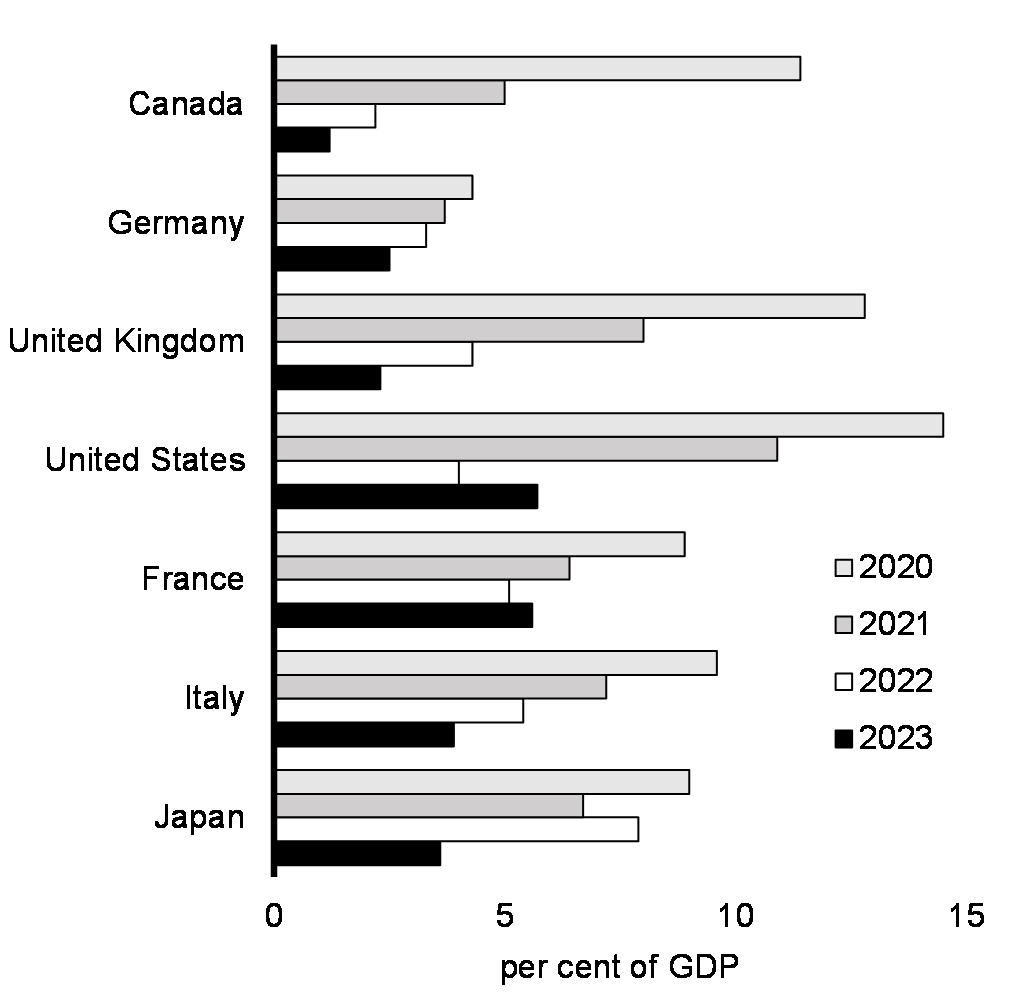

Compared to Canada’s international peers, the federal fiscal outlook and the better-than-expected provincial-territorial fiscal results position Canada to continue to have the lowest net debt-to-GDP ratio in the G7 (Chart 1.32). Canada is also expected to post the second largest fiscal consolidation (i.e., improvement in its budgetary balance) among G7 countries between the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic and next year, resulting in Canada having by far the smallest deficit of the group this year and next (Chart 1.33).

General Government Net Debt Forecasts, G7 Countries

General Government Deficit Forecasts, G7 Countries

Report a problem on this page

- Date modified: